KATOWICE (Poland) - UN talks meant to step up the global fight against climate change look set to go into extra time, as disputes between rich and poor nations held up agreement on a deal three years in the making.

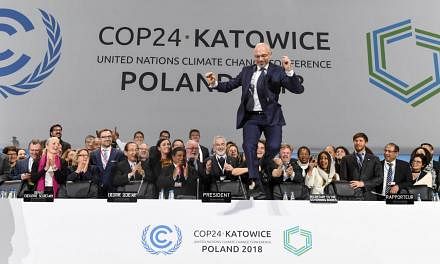

Delegates from nearly 200 nations are attending the two-week talks in the southern Polish city of Katowice to finalise a complex rulebook that would put the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement into action. Nations were set the task three years ago to work out the technical details but progress has been slow.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres arrived at the talks on Friday (Dec 14) to push for progress, his third visit to the conference.

Adding pressure on delegates, protesters at the venue called for stronger ambition in cutting emissions, while thousands of schoolchildren were urged to go on strike in Sweden and elsewhere, part of a global protest by young people angry over the lack of strong global action on climate change.

At the talks venue, students held up placards that read: "12 years left #climatestrike", referring to a finding in a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that the world had to cut carbon emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 to have a chance of limiting warming by 1.5 deg C.

The talks have made progress on the rulebook, with the draft spanning 144 pages, less than half what it was previously. But deep disagreements and mistrust between developed and developing nations have bogged down progress on several key areas, particularly the concepts of finance and ambition.

The Paris pact outlined a broad architecture in which all nations cut planet-warming carbon emissions based on their own national action plans. These are meant to be periodically strengthened and regularly reported and assessed.

The aim of the Paris deal was to develop one reporting and review system for all nations with some flexibility built in for countries who need it based on special circumstances, such as least developed countries and small island developing states.

In Katowice, there has been a strong push to allow for different capabilities and reporting capacity for poorer nations. There has also been disagreement over exactly how countries should account for their greenhouse gas emissions, and how the progress in meeting their national action plans should be measured, verified and by when.

But there was relief that text on reporting requirements was looking to be in good shape.

Ms Melissa Low, a research fellow from the National University of Singapore who is following the negotiations closely, said the text signified a compromise between nations.

However, the perennial dispute on finance for poorer nations remained a concern. Rich nations have been under pressure to be more transparent about the types of climate finance and the system to track and report it to ensure the agreed goal of US$100 billion (S$137 billion) a year from 2020 is adhered to by rich states.

Mr David Levai, who is lead for international climate governance for think-tank Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations, said of the latest draft text: "We have seen that climate finance is going to be flowing, and on that front, that there will be a continuation of flows from north to south... The next two years are crucial, as finance is definitely the leverage to unleash further ambition from countries. If they feel they can be supported, they will be happy to drive their ambition upwards."

However, Mr Harjeet Singh, global lead on climate change for ActionAid, said the devil was in the details.

He told The Straits Times: "We thought there would be stronger language around new and additional overseas development assistance. Instead, what we have now are grants, loans, guarantees, insurance... which means that going forward, developed countries can show that anything they are doing is climate finance. This indicates that there will be no real US$100 billion, no real action."

Mr Levai said a range of financial tools - whether it be direct aid, loans or investments - are needed for different countries and for different solutions. He said: "Some projects are profitable, such as investments into renewable energy, while in other areas such as adaptation, there are little financial returns and it is difficult to get private sector support. In those cases, the most adaptive tools will be grants.

"There has to be a whole panel of solutions. The level of finance has to be commensurate with the change that needs to happen."

Perhaps the most strident call from vulnerable nations, green groups and protesters is that the talks need to end with a rulebook that ramps up ambition in cutting global emissions, speeds up the phasing-out of coal - the most polluting of fossil fuel - and makes strong reference to the UN climate panel report.

IPCC's October report has taken centre stage at the talks because it sets out clearly the risks of warming beyond 1.5 deg C and that there is very little time left to make unprecedented changes to societies to avoid a climate catastrophe.

"The Paris Agreement was adopted only three years ago but countries are already trying to undermine the strong calls for action that this agreement entailed," said Ms Kim van Sparrentak, a delegate of the Federation of Young European Greens, at a press conference on Friday. "This is not about numbers, years and degrees. We are here talking about humans lives and human rights," she said.