A schoolboy athlete with a love and respect for sport – President Tharman

In an exclusive interview at the Paris Olympics, President Tharman Shanmugaratnam speaks to assistant sports editor Rohit Brijnath about his respect for athletes, his enduring love of sport and how he believes it shapes us as people.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

President Tharman Shanmugaratnam dining with Singapore athletes at the Olympic Village in Paris.

PHOTO: MDDI

Follow topic:

PARIS - The scene is elegant and telling. The man working late into the night at home on his computer. A serious man doing serious things. Yet next to him is a second screen and occasionally the sound alerts him, as it does in sport, that something exciting is happening. And so as he works, the President of Singapore also looks. “You can tell yourself,” he smiles, “that you’re multitasking”.

President Tharman Shanmugaratnam, 67, who sketched this image of himself watching sport, is a man of multiple interesting parts. He is also, how should one say this, just like you and me. A sports fan who happens to be president. He thinks Mohamed Salah has genius, leans towards the underdog, is a believer in the power of sport and is a father who knows that Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, the brilliant Jamaican sprinter, had better be spoken of with respect.

“(Watching sport) is a family thing,” Mr Tharman told The Straits Times in an exclusive interview during the ongoing Paris Olympics. “We are always exchanging videos. My daughter sends me stuff on her favourites.” And, he chuckles, “I never dare utter a word of doubt about Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce because it’ll lead to an immense argument with my daughter.”

The President’s love of sport reflects in his detail. He knows Fraser-Pryce’s age (37) and that she (1.52m) isn’t tall for a sprinter. He talks about 400m runner Wayde van Niekerk, who grabbed gold at Rio 2016, and mentions he won from the outside lane. I had to look it up later. The conversation happily lurches from C. Kunalan to Muhammad Ali and he has a feel for the little enchantments of sport. Its characters, its art, its glues and its teachings.

Some people view sport as frivolous or a mere pastime. But when Mr Tharman speaks of athletes, you can hear in his voice both affection and respect.

“They’ve got a flair of their own,” he says. “Different people have different skills and forms of genius even. And sports, like the arts, like adventure or entrepreneurship, are ways in which these skills and talents and different unusual abilities surface. And there’s something very democratic about that in a society.”

Every arena is a classroom and sport carries to us an education not always found elsewhere. “I think it has great value,” the President says. “It develops resilience and it develops an ability to appreciate others in the team. That’s the value it brings for individuals themselves.”

But it is, he adds, more than that. “I think it creates a unique emotional pulse in all of us. It rouses people. It helps create respect for people who have these different skills... Plus, I would add, it has the potential to develop multiracialism.”

On a greying Parisian afternoon, before the Olympic opening ceremony,

“I’ve been following the Olympics since young,” he says. “The world record is usually faster or further or higher than the Olympic record. But there’s something about the Olympics that is unique, something more difficult because it’s more intensely emotional and psychological, not just a competition of power or technique.

“And not everyone has it in them to win in the Olympics, even if you’re the superior athlete. Because there’s something about the Olympics that brings out something extra. Sometimes an underdog who has something extra.”

The day before our interview, Mr Tharman met athletes from Singapore and pictures emerged of a man listening to the stories of his fellow young citizens. “I’m usually listening,” he says. “The last thing we want to do is to put pressure on our athletes, about how far you expect them to go. They’ve got their own aspirations, their hopes, and they will all have their own measures of what success means.

“For some, just achieving their personal best against the best in the world is an achievement. Just getting to the Olympics is an achievement, particularly for someone from a small country. Some others might want to get to one of the final rounds. One or two might even be aspiring for a medal and may have a good chance. But that’s for each of them to shape. So the last thing I want to do is say, ‘I hope you get the gold, or hope you make it to the semi-finals’.”

Sport was the only subject of our discussion and his nuanced appreciation of it comes from a boyhood spent under the sun and rain. As a schoolboy, he says, “I filled up all my time with sports”. He played hockey, football, athletics and cricket “at a competitive level, for school or combined schools” and also sepak takraw, volleyball and rugby.

His hockey and football positions?

“Midfield or fullback.”

Then, with a twinkle, he adds, “I never felt I had the killer instinct to be a centre forward.” Instead, he loved the geometry of football, the passing of the ball into space. He was tall when he was very young, offering him the gift of reach, but it came with a minor complication. “I always had to bring my IC for inter-school matches until I was 14 because they had to check to make sure that I was in the right division.”

In an early sign of an organised man, he says, “I kept a small diary when I was in secondary school. Just so that I knew what games I played and where. And I remember looking at the diary at the end of the year and found that I’d played sports every day of that year, including Sundays, except for three days.”

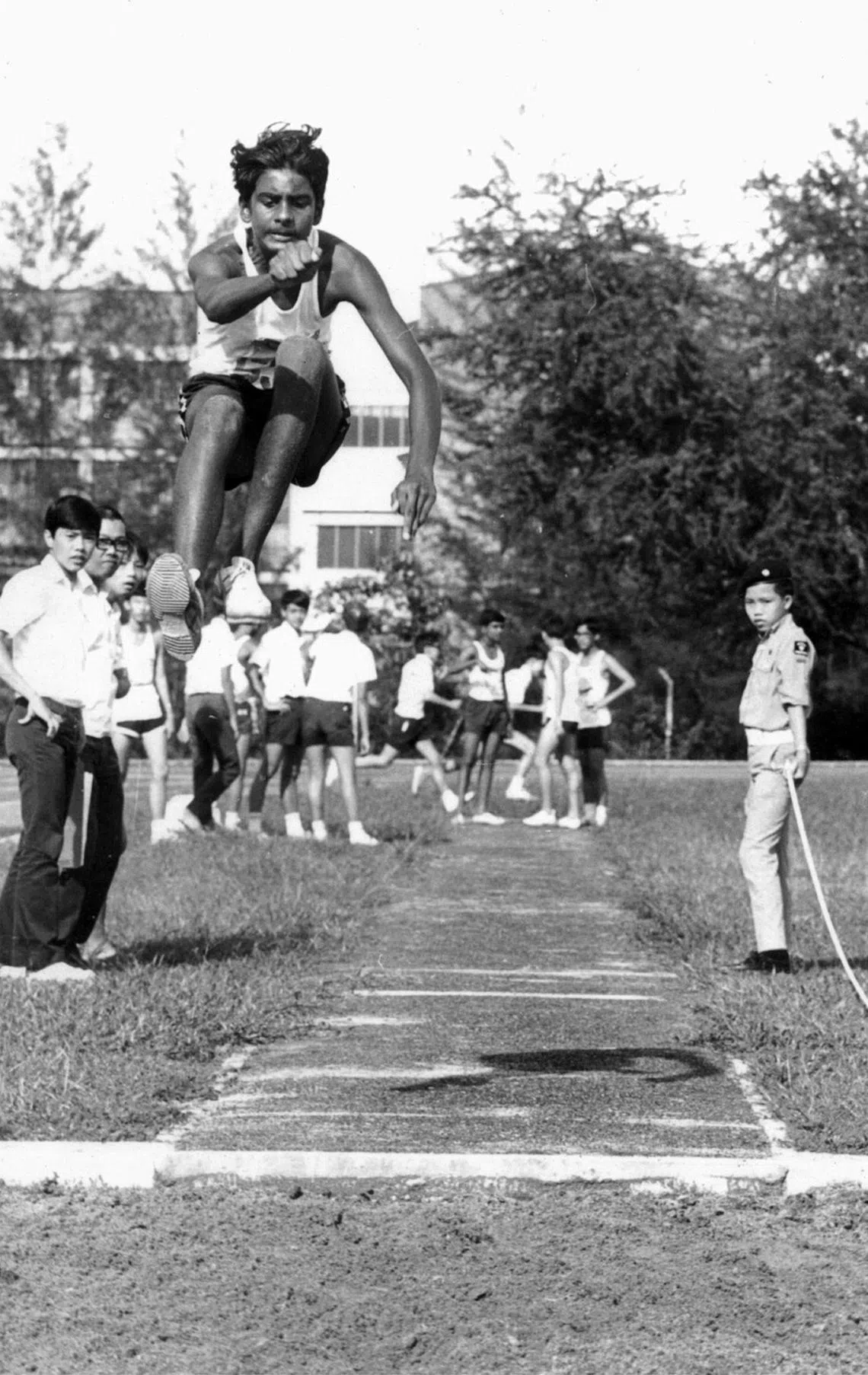

As a schoolboy, President Tharman Shanmugaratnam says, “I filled up all my time with sports”.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THARMAN SHANMUGARATNAM

Only later, when boyhood has passed, when wisdom arrives and we see the past clearer, do those of us who played sport see how it formed us. “You realise,” explains the President, “many years later that (it) shaped the way you think about people and the way you deal with life.

“In those days when you played inter-school, you were playing with schools from all over the island. So for instance, in hockey, one of the formidable teams in secondary school hockey was Naval Base (Secondary School). Now, Naval Base in those days had lots of kids who came from some very tough backgrounds.

“So you get to know them. Different races, different social backgrounds all the time, and you only realise much later that that’s what sports gave you. It helps knowing that there was always someone else who was better than you, and they came from very different backgrounds.”

Sport alters humans without us being actively aware of it. Its unwritten laws and virtues slowly and quietly seep into us like water into the ground. Another example of what Mr Tharman refers to as the “unforced lessons” from any athletic activity is that “you never keep winning in sports”.

“It’s impossible to keep winning. You win and you lose, even if you hope to win more often than you lose. And it builds resilience in you without you realising it at the time.

“When you train the entire season, starting early, starting November the previous year, week after week, and you reach the finals or semi-finals, and then you lose. That’s a great experience to have as you grow up. To be gracious as a winner, and to develop the resilience of someone who didn’t win but respects the winner.”

Sport charms and also cuts, it is the canvas of artists and grinders, it is where character is peeled back as humans push mightily at their limits. It is this “sheer human virtuosity” that captures the President. He loves football, for instance, but not any particular team, just the intricate beauties of the game itself. As we chat about football and Lamine Yamal’s wonder goal at the Euro,

“Sports are never just about physical ability. Some people are unusually well endowed physically, they can run faster, they can jump higher. (But) it’s not just physical, it’s actually intrinsically mental.

“If I take the example of field sports like football or hockey. So much of the game is not about the goals, but the passes that eventually lead to a goal. How long to hold the ball before making a pass? How powerful should the pass be, and exactly where do you place it so you are cutting through the defence and your teammate can get to the ball before anyone else. It’s instant decision, with multiple calculations, while everyone is moving.”

As president he is a role model, but as a human he has his own list of heroes. They lie closer to home, and he recites their names – an incomplete list, of course – as if summoning old friends from a favourite cupboard in his memory. Kunalan, Glory Barnabas, Chee Swee Lee, Heather Siddons, P.C. Suppiah, K. Jayamani, Melanie Martens, Farleigh Clarke.

They trained, he once wrote on Facebook and mentioned again in our interview, after work, often taking two buses, their funding scant, but wearing a rugged cloak of “old-fashioned grit”. Records were set that generations could not shake. “Chee Swee Lee’s 400m record lasted almost half a century. How did they do it with so little?” he wonders.

And yet he is encouraged about the present. “I think we’re seeing that X factor being rekindled. When Joseph (Schooling) did what he did, when Shanti (Pereira) does what she does, or Max Maeder does what he does, it does so much to inspire a whole generation. And with the advantage now of better funding, facilities, first-class coaches, physiotherapists, a very supportive environment, I believe our best years are ahead of us.”

As the interview winds its way through 54 minutes, I get glimpses of the fan inside the President. I see traces of the romantic in him, a man who leans towards team sports, grit and the graceful loser.

He is back home now and an image persists of him at night, scrolling through old relay clips on YouTube and studying the drama of the world at play at the Olympics. He is a man of high office but also a proud product of the everyday field.