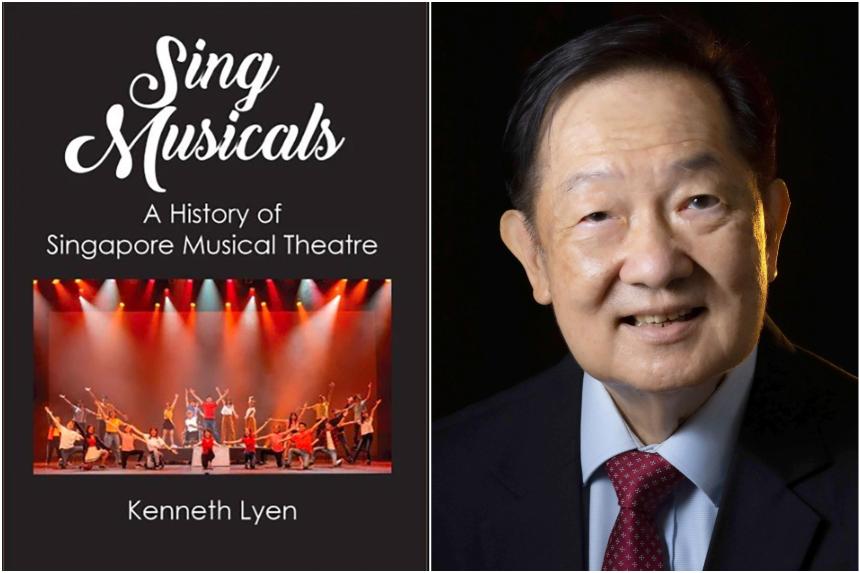

Sing Musicals: A History Of Singapore Musical Theatre

By Kenneth Lyen

Non-fiction/World Scientific/Soft cover/168 pages/$34/Epigram (str.sg/ipNx)

2 stars

For Arts’ Sake: Memoirs Of A Singapore Arts Manager

By Juliana Lim

Biography/Talisman/Soft cover/254 pages/$32/Epigram (str.sg/ipNf)

3 stars

From Keroncong To Xinyao: The Record Industry In Singapore, 1903-1985

By Ross Laird

Pop culture/National Archives Of Singapore/Hardcover/323 pages/$49.68 with GST/Books Kinokuniya (str.sg/ipNY)

4 stars

A trio of books addressing various aspects of Singapore’s cultural landscape have hit the bookshelves.

The varying quality of the writing, research and content is a vivid illustration of the gaps in Singapore’s writings about its cultural history.

That there is a dire lack of resources documenting and critiquing the country’s cultural production is no surprise to anyone in the arts community.

While it may seem like a niche interest, research and writing about a country’s cultural history are an integral part of building knowledge, interest and pride in its unique identity as well as understanding how that identity has been built.

These three books attempt to document different aspects of Singapore culture.

Consultant paediatrician Kenneth Lyen, a familiar face in the theatre scene, attempts a recap of musicals produced in Singapore theatre over the years.

Juliana Lim’s memoir looks back at her career, in the public and private sectors, which led her into the then-unknown field of cultural policymaker and arts administrator.

Last but not least is Ross Laird’s heavyweight tome, which scours the depths of the National Archives of Singapore’s collection for a history of the country’s record industry.

Lyen’s book is evidently a labour of love. The author is a composer who has written music for both amateur and professional productions, and his love of musical theatre is undisputed.

The book, however, suffers from an identity crisis, lacking the analytical depth one might expect from the subtitle, A History Of Singapore Musical Theatre, while being too niche to appeal to a broad reading audience.

There is a brief attempt at defining what a Singapore musical is. But most of the book is dedicated to a listing of musicals staged here over the years, along with a brief synopsis of each work.

If the intention is to create a definitive reference text, then there should be more academic rigour to the categories.

The inclusion of Toy Factory Productions’ award-winning 1994 play Titoudao in the non-English musicals chapter raises eyebrows. Hokkien opera excerpts do not a musical make.

One might also quibble with the inclusion of operas – arguably, a different genre of theatre altogether – and amateur school productions.

What does emerge from Lyen’s loving annotation of shows is the unmistakable growth of the Singapore theatre industry over the years.

This impression of exponential growth is also a distinct motif in Lim’s memoir.

Like Lyen’s book, this is evidently a personal passion project and, like the former, it suffers from a lack of editing, which might have caught some of the more egregious grammar and spelling errors, besides tightening the narrative.

Nonetheless, Lim’s point of view is an essential one, as she has had a hand in the formation of cultural policies and initiatives in her capacity as a civil servant in various government bodies and ministries over the years.

She managed several portfolios, including culture at People’s Association in the late 1970s, before moving on to the then Ministry of Community Development, Ministry of Information and the Arts as well as Singapore Arts Centre, the precursor of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

She has had a front-row seat to some of the most critical developments in Singapore’s arts landscape, ranging from the programming of the Singapore Arts Festival to the introduction of the arts housing scheme to the building of the multi-million-dollar Esplanade.

Arts insiders will probably scour this memoir, hoping for further insights into certain aspects of cultural policymaking.

But Lim’s memoir is no lurid tell-all. Instead, it is an affectionate, rather rambly account of her long career learning on the job as an arts administrator, at a time when the job description did not exist in the nascent arts scene.

There are some interesting nuggets to be gleaned from her narrative, although this can be frustrating as she leaves out some of the juiciest details.

A passing anecdote about a Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau looking into a complaint against a Ministry of Culture staffer is one such unsatisfying shocker.

Most of her anecdotes focus on her work and colleagues, with personal stories about encounters with ministers and late president Ong Teng Cheong.

One of the revelations here is how some of the challenges the arts scene faces today have remained unchanged despite the startling advances of the past 50 years: trying to convince people of the necessity of the arts, how the posting churn of bureaucrats can have unintended consequences on cultural policies, and the eternal battle between economics and arts.

The issue of economics, as well as technology, looms largest in Laird’s painstakingly researched book.

Bound handsomely in hardcover, this tome is the most meticulously researched of this clutch of books. So much so, it might be too intimidating for the average reader.

But its accessibility is aided by the many intriguing photographs of rare vinyls and album sleeves from the National Archives’ collection.

The production of shellac and vinyl discs as well as the recording of musicians in Singapore are not well-known history. So Laird’s detailed listing and chronology of various international and local labels may come as a surprise to many readers.

American inventor Thomas Edison’s phonograph, patented in 1878, was demonstrated in Singapore the following year, reflecting the city’s position as a major port city with open trade and technology flows.

The development of the recording industry here was also contingent upon its location, with international representatives from various companies taking advantage of Singapore’s location and cosmopolitanism to record singers in multiple languages from various neighbouring territories.

While a good chunk of the book is dedicated to tracing the mind-boggling number of international recording companies, there are plenty of anecdotes about Singapore’s pop-cultural landscape that will engage the general reader.

One of the most intriguing strands is the relationship between politics and popular culture.

For example, the Japanese Occupation led to the suspension of recordings as well as the destruction of paper documentation.

But the Japanese also introduced the idea of “shiokudo”, Japanese restaurants with musicians playing live. These “singing cafes” became a popular trend in the post-war era.

Again, economics and sustainability played a critical role in the creation of Singapore’s pop scene.

Small local labels thrived in the pre-war years by recording popular favourites from keroncong and Chinese opera singers.

In the post-war years, home-grown musicians experienced astonishing success, with records selling in the tens of thousands.

But those glory years were cut short by disruptive technologies – vinyls were displaced by cassettes, and rampant piracy ate into profits and made music an unsustainable career.

There is an ironic familiarity to this cycle of technological progress and industry disruption as home-grown musicians today are facing similar issues with streaming and fragmentation.

Yet, the book is a vivid reminder that Singapore had, and still has, talent.

While imperfect, all three books succeed in capturing swathes of hitherto under-exposed areas of Singapore’s cultural history and prove there are rich veins to be tapped.

If you like this, read: Theatre Life: A History Of English-language Theatre In Singapore Through The Straits Times (1958-2000) by Clarissa Oon (Singapore Press Holdings, 2001, National Library, go to str.sg/ipfG). It is an introduction to the development of theatre and theatre groups in Singapore in the second half of the 20th century.