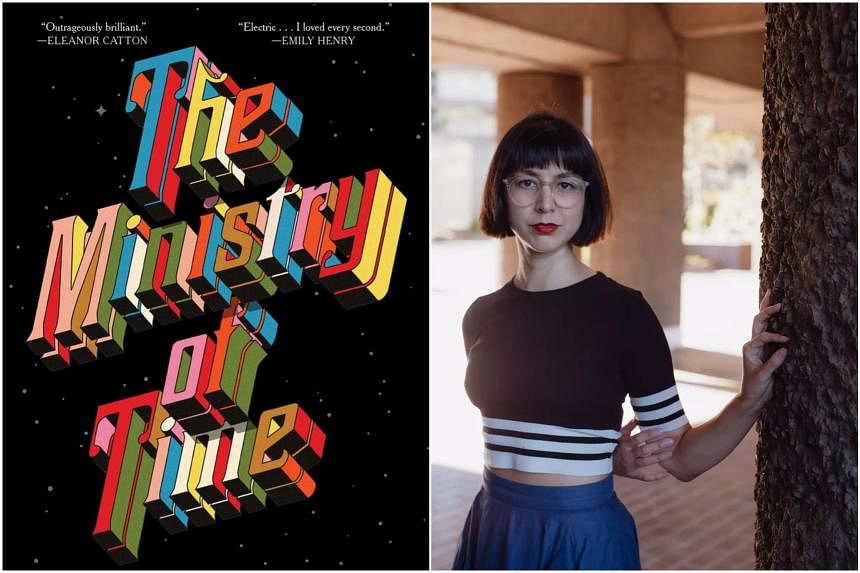

The Ministry Of Time

By Kaliane Bradley

Fiction/Sceptre/Hardcover/353 pages/$28.86/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3Wqz7sT)

5 stars

What would a Victorian-era polar explorer think of the present day? How would he react to air travel, women’s rights or Spotify?

This is the loose premise of British-Cambodian writer Kaliane Bradley’s extraordinary debut, The Ministry Of Time, yet it is so much more than a fish-out-of-water time-travel tale. It is a gripping, high-octane spy thriller; a dark workplace comedy; a powerful meditation on climate crisis and displacement.

It is also, most importantly, a love story. That it manages to fold so many genres and themes into one smooth package is part of its marvel.

In the near future, the British government has gained the power to time-travel. As a test, it has gone back into history and retrieved select individuals – or “expats” – who would have died in their original timelines, such as a woman from a plague-house in 1665 or a soldier on the frontlines of World War I in 1916.

The novel is narrated by an unnamed civil servant who has joined the eponymous Ministry as a “bridge” to one such expat, Commander Graham Gore.

In the real world, Gore was one of the 129 men on the ill-fated Franklin expedition in the 1840s to find the Northwest Passage in the Arctic Ocean, none of whom were ever seen again.

The narrator’s role is to help Gore acclimatise to the 21st century. Over the course of a year, they cohabit in a house in London as she tries to teach him about germs, the collapse of the British Empire and how to use a smartphone.

She also monitors him for her employers, for whom he is no more than the subject of an experiment. Should the expats survive, her boss tells her, “you will have the lovely warm glow of having contributed to a humanitarian project”.

And if they die? “Then you will have contributed to a scientific project.”

Displacement features, too, in the narrator’s own family history. Though she can pass for white, her mother is Cambodian and arrived in Britain as a refugee from genocide.

The narrator treats her marginal identity and inherited trauma with a wry detachment that verges on the manipulative. “I could be a little exotic,” she quips, “just enough to bring up in my annual appraisals if a raise or title change was under discussion.”

This presents, nevertheless, a web of frictions she must navigate with Gore. How do you explain racism to a Navy man whose career highlights included capturing the port of Aden, in present-day Yemen, for the British Empire and who unironically refers to you as “half-caste”?

Yet, as the seasons change and the weather fluctuates alarmingly – terrible heatwaves, catastrophic storms – the tension between them evolves into something else.

Meanwhile, the project starts to unravel and the narrator begins to suspect that the Ministry has sinister motives for pursuing time-travel.

The novel is deftly plotted and dryly funny. Much of the humour stems from historical figures encountering modern life: Margaret Kemble, lately of the 17th century, declares Facebook to be “for folk who prefer to have their minds filled with soft oats and whey”, but takes swiftly to Tinder.

Bradley’s prose is witty; she has a gorgeous turn of phrase. I started writing down lines that stood out to me, but the book is so rife with them, I had to give it up.

I remain struck, however, by how the narrator’s mother “persistently carried her lost homeland jostling inside her like a basket of vegetables”. One will recall this, later, when the narrator tries to describe what it feels like to fall in love: “He lives in me like trauma does.”

Bradley has taken the most trite of tropes – a love so strong, it can change the course of time – and injected it with a fresh, compelling urgency. It sensitises one to how the future is constructed: a series of choices, monumental or minute, intended or unintended, all irrevocable.

The reader is made hyper-aware of time as a resource that is running out, not just for the characters so desperately trying to mine it, but also in the reality of the world humanity is so disastrously devouring.

The moment I finished this novel, I immediately started reading it again to see where all the seams fit together. Yet, as the narrator learns the hard way, “you only get to experience your life once” – and you can only read this novel for the first time once. If that experience is still in your future, I envy you.

If you like this, read: An Ocean Of Minutes by Thea Lim (Quercus, 2018, $36.76, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3Qt22Jc). In an alternate 1981, a viral pandemic spreads across America. To obtain a vaccine for her sick boyfriend Frank, Polly Nader agrees to travel 12 years forward in time as a bonded worker. But when she is re-routed mid-flight, she arrives alone in an utterly changed America where Frank is nowhere to be found.