WASHINGTON (NYTIMES) - With Ms Christine Lagarde, the current leader of the International Monetary Fund, poised to become the next president of the European Central Bank, the big questions are who would succeed her and whether the United States would break with tradition and try to install an American in the post.

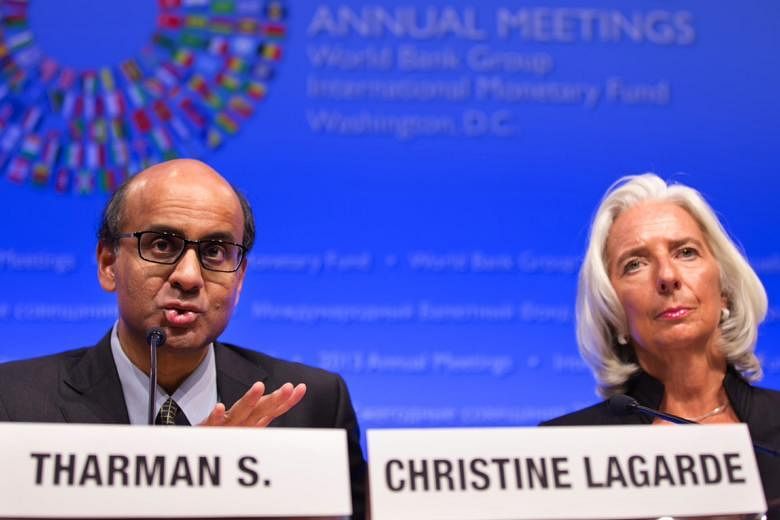

The top job at the IMF has traditionally gone to a European but there have been some suggestions that the practice be changed to reflect Asia's growing influence in the global economy. Among the names that have emerged on early shortlists are Singapore's Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, who was the chairman of the International Monetary and Financial Committee; Mr Agustin Carstens, a former deputy managing director of the monetary fund; and Mr Mohamed El-Erian, the former chief executive of Pimco.

On Tuesday (July 2), European officials nominated Ms Lagarde to succeed Mr Mario Draghi as the European Central Bank's president. Ms Lagarde, a stabilising force who has lent star power to the IMF since taking over as its managing director in 2011, plans to step away from her responsibilities while the nomination process moves forward.

The expected transition of power at the fund comes as the global economy slows and protectionism increases amid President Donald Trump's multi-front trade war. The next director of the fund will have to confront economic woes in Argentina, Venezuela and Turkey, as well as take over the kind of multilateral institution that Mr Trump has long criticised as overstepping its authority.

"The key challenge for the next IMF head is how to maintain the institution's relevance, influence and legitimacy in a world where multilateralism is breaking down amid trade tensions and shifting geopolitical alliances," said Mr Eswar Prasad, the former head of the IMF's China division.

"The IMF is the epitome of multilateralism in international finance, but it suffers from marginalisation by the key advanced economies, a pool of resources dwarfed by global capital flows, and lack of trust among emerging market economies."

By tradition, the leader of the World Bank is an American, and a European heads the IMF. When the World Bank president position came open, Mr Trump tapped Mr David Malpass to run the institution. But there has been some speculation that Mr Trump might try to break with that longstanding practice with the IMF.

Its 24-member executive board selects the managing director, and the appointments have always been decided by consensus. Ms Lagarde was chosen after a six-week selection process.

"I suspect the Europeans are scrambling as we speak to ensure that Europe retains that position," said Mr Tim Adams, the president of the Institute of International Finance who was the Treasury Department's undersecretary for international affairs during the George W. Bush administration.

Most expect that the monetary fund will stay under European leadership because there was little foreign resistance to Mr Trump's choice of Mr Malpass, a former Treasury Department official who had a long career on Wall Street.

Apart from Mr Tharman, Mr Carstens and Mr El-Erian, Mr Mark Carney, the departing governor of the Bank of England, is also among those rumoured for the job. Mr Carney is a British citizen who was born in Canada. However, with Britain in the process of separating from the European Union, it is not clear if he would satisfy desires for a European managing director. Mr Carney, who also has an Irish passport, could be nominated by another country, but his path to the job would still depend on some political wrangling.

"Then it comes down to, can the UK build an international coalition of support?" said Mr Vasuki Shastry, an associate fellow for the Asia-Pacific programme at Chatham House who worked at the IMF for 16 years until 2017.

"The European vote is absolutely crucial. The Europeans have a higher voting share than the US."

The IMF monitors the global economy and financial system and provides loans to countries that are struggling to meet their debt obligations. Because it works so closely with emerging economies, there are sometimes suggestions that the fund's director should come from outside the US or Europe. However, because those countries tend to be more dependent on the fund, they are often reluctant to press the issue.

"While they can see that it makes no sense for every director to be European, nonetheless they recognise that to make a fuss about it is to invite revenge so they don't," said Mr Peter Doyle, an economist formerly at the fund.

Although the stature of international financial institutions has waned in recent years, Ms Lagarde's tenure at the fund has widely been viewed as a success. She replaced Mr Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who resigned amid a sex scandal, improved the fund's transparency and helped steer Europe through a debt crisis.

"This time around, they're really building on Christine Lagarde's reputation," Mr Shastry said. "Someone of international stature, well known in the economics community."