GLASGOW - The hour of 6pm on Friday (Nov 12) - the time by which COP26 president Alok Sharma had hoped to deliver a deal - has come and gone, with still no deal on the table from the ongoing United Nations climate summit in Glasgow.

The third version of the COP26 draft cover decision text - or "package deal" that outlines the compromises made on various sticking points - was published at 9am Saturday morning Glasgow time (5pm Singapore time). But this is subject to further revisions.

The annual climate meetings are notorious for overrunning.

On Friday, the day the conference is scheduled to wrap up, the UN sent an e-mail to delegates informing them about the extension of the validity of conference passes, saying accreditation badges are valid for 12 hours "after the final gavel marks the close of COP26".

But there is no indicator yet when this could be.

Negotiators and ministers from almost 200 nations who have gathered in the Scottish city still need to come to a compromise on a few key issues.

There seems to be an appetite for consensus, The Straits Times understands, but countries still need to find "landing zones" on a few key issues before the Paris Rulebook can be finalised.

This finalised Rulebook - which will help get the 2015 Paris Agreement move from aims to action - is a key aim at this meeting.

Remaining sticking points include climate finance to help developing countries tackle climate change and address loss and damage, as well as the development of rules governing international carbon markets.

What are carbon markets?

In such a market, carbon is commodity-du-jour.

Each carbon credit refers to one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) that is removed from the atmosphere (a forestry restoration project), or prevented from being produced (a renewable energy plant).

These credits can be bought by an emitter elsewhere to offset its own emissions.

The 2015 Paris Agreement had outlined in broad strokes the vision of a global trade in emissions reductions centred on carbon markets.

Countries can trade emissions reductions among themselves, or private entities can invest in projects and sell the credits, or there could be other approaches that assist other nations but do not involve any trading.

This vision is outlined in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, making up nine paragraphs. But detailed rules of creating these new markets was left to future discussions to figure out.

In Glasgow, those discussions are still ongoing, a testament to the complexity of divergent views on how to create these markets.

How can carbon credits move across borders?

There are three mechanisms encoded in Article 6. Two are market approaches and one is a non-market approach.

1. Country-to-country trade in emissions reductions

This is the first market mechanism, and involves the trade in credits between countries.

For a country to have credits to sell, it must have achieved the targets that it set out under the Paris Agreement. Any "overachievement" - in terms of emissions reduction, for example - can be sold to another country that did not meet its climate goals.

This is encoded in Article 6.2.

2. Purchase of credits from carbon reduction projects

This second market mechanism brings in the private sector, although a UN body will oversee it.

Article 6.4 will essentially allow countries to buy credits from carbon reduction projects from almost anywhere in the world.

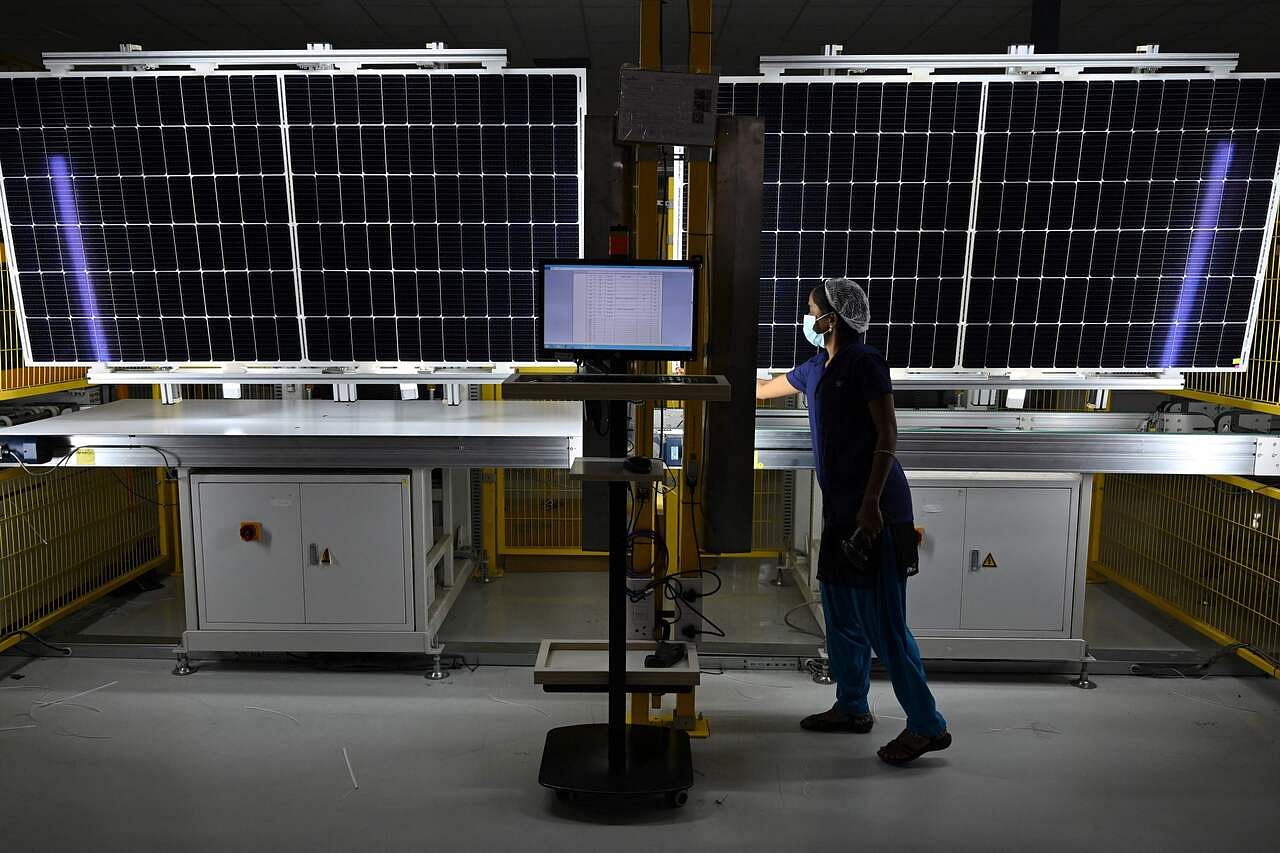

These projects could be funded by other governments or the private sector, and include renewable energy projects, large-scale energy efficiency efforts such as more efficient air-con chillers or lighting upgrades for buildings, as well as nature-based investments, for example, restoration of mangroves or peat-swamp forest.

This new market - referred to as the Sustainable Development Mechanism - is considered the successor to the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol was the world's climate pact before the Paris Agreement.

But the Paris Agreement also states that this market should deliver an "overall mitigation in global emissions".

This means that the market should go beyond zero-sum trading, where emissions in one place are merely offset by reductions elsewhere, to lead to real reductions in the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

How to do this, though, is still being hotly debated.

3. Climate cooperation

Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement covers non-market approaches that encourage emissions reductions. This does not involve the trading of emissions reductions.

According to climate news site Carbon Brief, an example could be a country supporting a renewable energy scheme overseas via concessional loan finance, but there would be no trading of any emissions cuts generated.

Why are carbon markets important?

These negotiations are vital for a number of reasons.

A well-designed carbon market could allow countries to offset their emissions in a cost-efficient way.

For instance, it may be challenging and expensive for a country to completely overhaul its power grid in the near term to run on renewables. Instead, the nation could opt to do so gradually, and offset any of its emissions in the interim by buying offsets on the carbon market.

Such markets can also unlock billions of dollars in investment in projects that reduce emissions, thereby helping nations meet their climate action plans under the Paris Agreement.

Those financial flows could especially help developing nations, many of which are strapped for cash to invest in renewable energy, forest protection and restoration, energy efficiency and other steps that could cut greenhouse gas emissions.

But it is crucial that any such projects and emissions reduction transfers are genuine, verifiable and really do lead to cutting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas pollutants.

They are not meant to allow nations or companies to continue to pollute and merely buy their way out of progressively deeper emissions reductions.

What are the issues left to be worked out?

1. Preventing double counting

The problem of double counting - where the countries selling the carbon credits count the savings under their own national targets , or sell the same credit to two different parties - is still being sorted out.

This double counting could apply to both market approaches.

In the case of Article 6.4, where the source of carbon credits are projects undertaken by the private or public sector, countries such as Brazil are saying there is no need for the host country to make corresponding adjustments to its own emissions inventory if it sells a credit to someone else.

Its basis for this argument lies in the way Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement is worded.

The paragraph states that carbon reduction projects will "contribute to the reduction of emission levels in the host party, which will benefit from mitigation activities resulting in emission reductions that can also be used by another party to fulfil its nationally determined contribution".

But double counting can also occur under Article 6.2, which is the market mechanism that allows a country which has met its climate pledge under the Paris Agreement to sell off any overachievement to someone else.

The crux of the matter lies in the different types of climate pledges made by countries.

Some nations set themselves economy-wide targets, but others set themselves sector-specific ones - for instance, emissions savings from their forestry or energy or waste sectors.

This allows countries that have set only sector-specific targets to cash in on emissions savings elsewhere without affecting their climate pledge.

Discussions are now ongoing to see how this form of double counting can be reduced.

2. Carry-over of credits from the Kyoto Protocol scheme

Under the Kyoto Protocol's CDM, which has been operational since the beginning of 2006, there are about 8,000 registered projects.

Many of them are in developing countries such as India, and include things like wind farms and solar projects.

But observers such as policy officer Gilles Dufrasne from the non-profit Carbon Market Watch said one outstanding issue is how the new Article 6 markets should treat the credits from the CDM projects, which "have generated billions of carbon credits of very low environmental integrity".

"It's a very political issue, how to deal with those credits," he said. This is because countries which host a large number of these CDM projects could stand to benefit financially with the sale of these legacy credits.

However, opponents of the carry-over of CDM credits say that allowing past credits to be sold will prevent new projects to reduce or prevent emissions from being developed.

There is also the issue of the quality of CDM credits.

These units are supposed to represent a tonne of CO2 each, but there is not yet agreement on whether they really do.

The main compromise being discussed now is to limit the projects that can transition from the CDM into the new Article 6.4 market based on the date they were registered.

"For example, saying that all credits that come from projects that were registered after 2016 would be transitioned into the Paris agreement," said Mr Dufrasne.

Another landing zone is to have a "use-by" date, where these credits must be used before the timelines set out under the current round of climate pledges, which is 2030.

But parties seem to agree on one thing, Mr Dufrasne said, which is that any CDM credits used in the Article 6 market will have to meet the finalised new rules set out under the Paris Agreement before they can do so.

3. Share of proceeds

Under the Kyoto Protocol's CDM, about 2 per cent of the trade in carbon credits is funnelled to the Adaptation Fund - which funds adaptation projects in countries vulnerable to climate impacts.

Adaptation strategies refer to efforts that can reduce the impacts of climate change on human societies, such as building sea walls to keep out rising sea levels, for instance.

Countries are generally agreeable to having a similar levy applied in the purchase of carbon credits from various projects (Article 6.4).

But the bone of contention now lies in whether such a levy should also apply when there is a country-to-country trade in credits (Article 6.2).

Developing countries, especially the small island states, are not seeing adaptation funding coming from other negotiation tracts at COP26 so they are holding the ground on this front, insisting that a share of proceeds from Article 6.2 trades apply as well.

Having this levy applied to both market mechanisms will also ensure that countries do not lean towards the market that does not have it. But wealthier countries are not receptive to this.

Another issue related to this share of proceeds is the automatic cancellation of some credits so net emissions savings are still achieved.

Developing countries, which are suffering the most from climate change impacts, say this will ensure an overall reduction in the amount of greenhouse gases being produced, instead of merely shifting the emissions from one place to another.