SINGAPORE - It is too early to tell if the new B.1.1.529 strain of the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, which has been classified a variant of concern (VOC) and named Omicron, will pose a real threat, said experts - but the world is taking its emergence seriously.

This strain was first detected in South Africa on Nov 11, and has also been found in Botswana and Hong Kong.

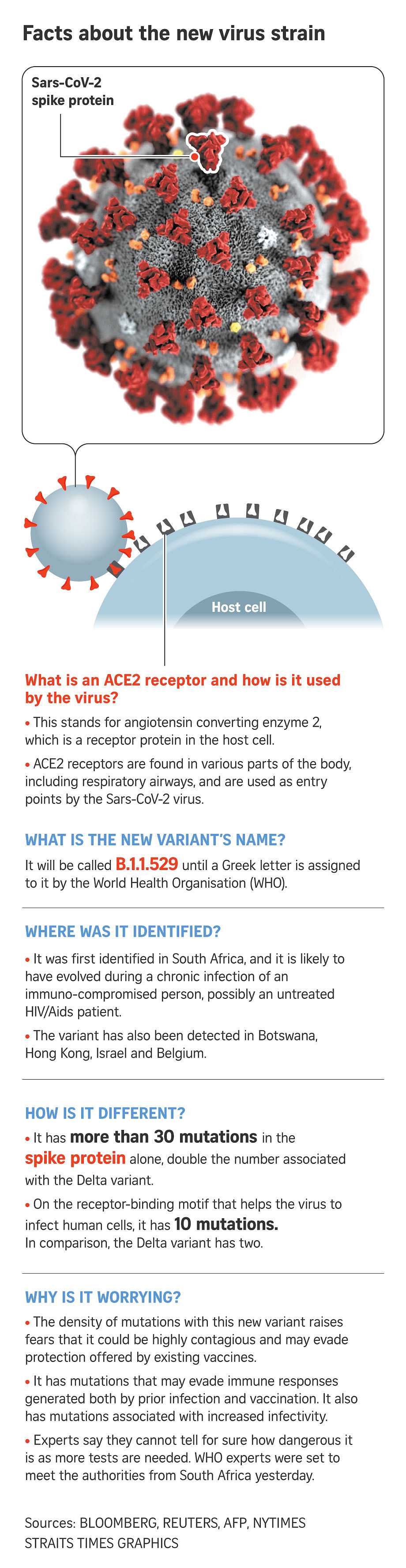

It has 32 mutations in the spike protein - about double that of the Delta strain, which now dominates Covid-19 infections around the world.

And this has scientists worried that the new strain may be more transmissible or evade the body's immune response of vaccinated or previously infected people, and thus spark a new wave of infections globally.

"The unique mix of mutations here is of interest as it comprises several that were previously known to improve the success of a virus," said Dr Sebastian Maurer-Stroh, executive director of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research's Bioinformatics Institute.

Spike proteins are the target of most vaccines as they are what the virus needs to enter the body's cells.

Professor Wang Linfa, an expert on emerging infectious diseases at Duke-NUS Medical School, however, said how big a threat it is still remains to be seen as there are three important key variables in play - its transmissibility, vaccine-escaping ability and virulence.

A variant that spreads easily but does not carry with it the potential for serious illness will not be of great concern.

The B.1.1.529 was classified by the World Health Organisation on Wednesday (Nov 24) as one of eight variants under monitoring - less than two weeks after the first mutated genome was sequenced.

On Friday night, the WHO raised it to the top level as a VOC, bypassing the middle "variant of interest" level.

It has been named Omicron and is the fifth VOC, and the fastest any emerging virus has shot to the top of the table.

The other four - Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta - took between two months and seven months from emergence to being declared a VOC.

The Delta variant had thousands of genomes sequenced before it was named a VOC.

In contrast, the new strain has 81 identified by genome sequencing so far - six from Botswana, two from Hong Kong and 73 from South Africa - said Dr Maurer-Stroh.

He is part of the global team that maintains Gisaid, the organisation that provides the shared genome platform for Covid-19, which now has 5.5 million sequenced genomes from around the world.

Associate Professor Hsu Li Yang, an infectious diseases expert at the National University of Singapore's Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said the emergence of the B.1.1.529 strain "certainly is similar to past VOCs, with an explosive rise in cases shortly after an earlier wave, albeit in a population where the vaccination rate is far below 50 per cent".

He added: "While the mutations and rapid spread suggest that it is highly transmissible, whether it is more virulent is unknown at this point in time, as mostly young people have been infected to date."

His colleague, Associate Professor Alex Cook, who is vice-dean of research, said case numbers in South Africa have been growing fast. This is "consistent with it being either more transmissible or better able to overcome existing immunity".

If it really is more transmissible, he said, "then we would expect it to be a matter of time before it spreads beyond South Africa's borders".

Professor Ooi Eng Eong, who does viral research at Duke-NUS Medical School, said mutations are expected, so it is important "not to get paralysed by news on new variants".

He added: "The virus cannot mutate in just any part of the spike protein. Some parts are highly conserved and mutations in this part could destroy the architecture and hence the viability of the virus."

Because some parts of the spike protein are immutable, our immune responses that target these parts of the spike protein would still be able to elicit protective effects against the virus.

People who have been infected - that's about 260,000 people in Singapore - would also have antibodies and T cells that target other parts of the virus beyond the spike protein. Changes in the spike gene sequence would not affect the immune response to the other parts of the virus, Prof Ooi said.

He added that while the virus has the ability to evolve, "we should remember that our immune system is quite sophisticated".

"It can kill viruses in many different ways, and some of these killing mechanisms are difficult to measure in the laboratory."

The article was edited to take in the new developments overnight from WHO.