As Singaporeans would have noticed in recent weeks, nothing encapsulates the intertwining of politics, technology and the environment quite like water.

This scarce resource first returned to the national spotlight last month, when Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad criticised the water supply deal between Singapore and his country, saying that the price at which water is sold to the Republic is "ridiculous".

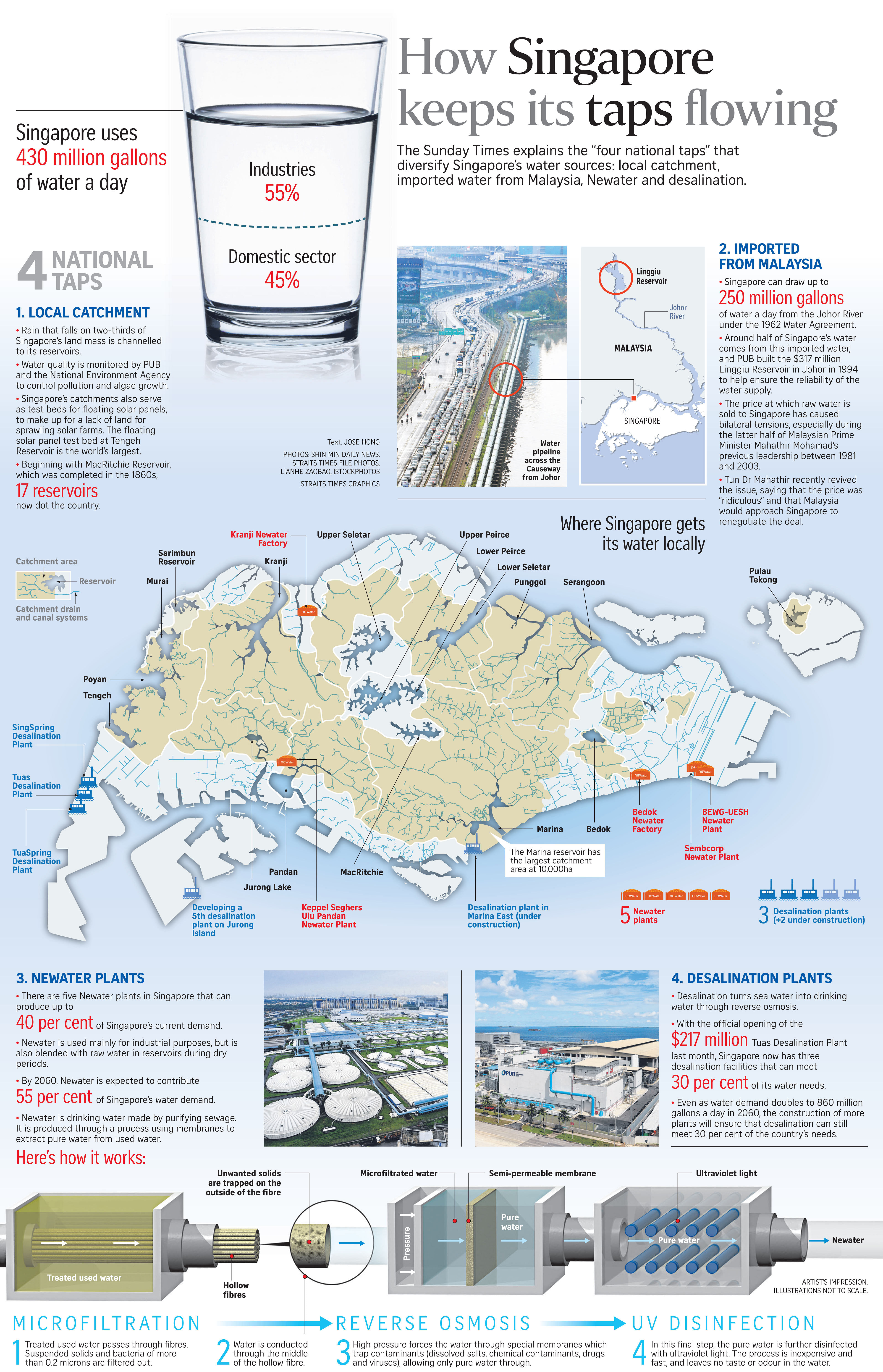

An agreement signed between Singapore and Malaysia in 1962 allows Singapore to draw up to 250 million gallons of raw water from Johor daily at three sen (1.01 Singapore cents) per 1,000 gallons.

Last week, Johor's Menteri Besar Osman Sapian upped the ante, saying the state hopes it can raise the price to 50 sen per 1,000 gallons.

Amid this unfolding situation, Singapore officially opened its third desalination plant in Tuas, which can produce enough water to supply 200,000 households. This is a noteworthy achievement many countries would have been proud of.

But far from chest-thumping, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli chose the launch of the facility to remind Singaporeans that water is still an existential issue for the Republic. He referred to a report by the World Resources Institute which said Singapore would suffer from extreme levels of water stress by 2040.

To be sure, Singapore's water supply faces a lot of challenges, including climate change, which is an ongoing threat, and supply from Malaysia, which may be vulnerable to the vagaries of political ties.

-

Bilateral issue bubbled up in 1998

-

Water also became a point of contention when Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad was last PM of Malaysia from 1981 to 2003.

In 1998, he had asked for a renegotiation of the 1961 and 1962 water agreements - which entitle Singapore to draw up to 250 million gallons a day (mgd) of raw water from the Johor River, for 3 sen per thousand gallons of raw water.

In return, Johor is entitled to a daily supply of treated water of up to 2 per cent or 5 mgd of the water supplied to Singapore, at 50 sen per thousand gallons.

Though Tun Dr Mahathir had raised the issue past the dates - 1986 and 1987 respectively - provided for in the agreements for price reviews, Singapore agreed to the renegotiation.

Over the span of four years, both countries held several rounds of talks on bilateral issues, which included the price of water.

Malaysia regularly asked to raise the price, and the matter became a sore point. In October 2002, Dr Mahathir decided to abandon the process.

In January 2003, then Foreign Minister S. Jayakumar made a statement in Parliament on the issue, speaking about the sanctity of the water agreements and giving a detailed chronology of the package negotiations involving the agreements. The Government also made public all correspondence on the matter, and released a booklet, Water Talks? - If Only It Could, to refute Malaysia's points.

This is an excerpt from the booklet:

"Briefly, in 1998, Singapore and Malaysia began negotiations on a 'framework of wider cooperation'.

"During the 1998 Financial Crisis, Malaysia wanted financial loans to support its currency; Singapore suggested that Malaysia give its assurance for a long-term supply of water to Singapore. Malaysia eventually had no need for the loans. Negotiations turned to other matters of mutual interest. In particular, Malaysia wanted joint development of more land parcels in Singapore in return for relocating its railway station away from Tanjong Pagar.

"Over the next three years, more items were bundled together to form a negotiated package, where both sides asked for and offered various concessions on several outstanding bilateral issues. One of the items added by Malaysia was a higher price for the water it sold to Singapore.

"Singapore's position has consistently been that neither Malaysia nor Singapore can unilaterally change the prices of raw water and treated water specified in the Water Agreements. Under the Water Agreements, Singapore pays Johor 3 sen per thousand gallons of raw water and Johor pays Singapore 50 sen per thousand gallons of treated water. 50 sen is only a fraction of the true cost to Singapore of treating the water, which includes building and maintaining the entire infrastructure of the water purification plants. The Water Agreements provided for a price review after 25 years. This would have been in 1986 for the 1961 Water Agreement and in 1987 for the 1962 Water Agreement. Malaysia chose not to review the price of water then. Malaysia has therefore lost its right to review the price of water.

"While we tried to negotiate on terms acceptable to both sides, Malaysia kept changing its negotiating positions on the package of items. On water, Malaysia's asking price kept increasing throughout the negotiations. It increased from 45 sen per thousand gallons in August 2000, to 60 sen in February 2001, to RM6.25 in September 2002.

"Finally, in October 2002, Malaysian Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad told Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong that Malaysia wanted to 'decouple the water issue' from the other items in the package. Prime Minister Goh told Prime Minister Mahathir that since Malaysia wanted to discontinue the package approach, Singapore would have to deal with water and the other issues on their stand-alone merits."

But it is also true that Singapore has made very significant advances over the years to diversify and secure its water sources.

WHERE THE WATER COMES FROM

After years of research and development, Singapore has strived to overcome its water dependency and turned this, ironically, to its advantage by establishing itself as a world leader in water treatment technology.

Today, Singapore has four water sources or "taps": imported water from Malaysia; Newater or treated used water; desalination or treated sea water; and local catchment water from reservoirs.

Investments in these four taps have been significant. For example, the desalination plants have cost between $200 million and $1.05 billion to build.

PUB also invested $9.9 billion in total in two phases of the Deep Tunnel Sewerage System, which will convey used water to reclamation plants to be treated and purified to become Newater.

Singapore gets the lion's share of its raw water from across the Causeway, largely from Johor's Linggiu Reservoir, which can meet 60 per cent of Singapore's water needs during times of normal rainfall.

With the agreement expiring in 2061, and with the expectation that water demand would have doubled by then, water planners in Singapore have long understood the need to build capacity ahead of time.

Early plans included the development of 17 freshwater reservoirs.

At present, two-thirds of Singapore's land area are water catchment areas, which PUB plans to raise to 90 per cent by 2060. Given Singapore's size, it has looked to the sea and to water reclamation as well.

Up until the early 2000s, Singapore was still heavily reliant on reservoirs or Malaysia's Johor River to meet its water needs.

Then, in 2002, a new tap came online. Using advanced membrane technology and ultra-violet disinfection, national water agency PUB could purify treated used water that has been rid of solid particles, as well as bacteria and viruses.

The end product: Newater.

There are now five Newater plants that meet up to 40 per cent of Singapore's water needs.

In 2005, a new tap was added to the mix - the first desalination plant in Tuas. With the opening of the third plant last month, up to 30 per cent of Singapore's water needs can now be met by turning sea water into drinking water. Two more such plants are in the works, in Marina East and on Jurong Island.

But both these water treatment methods require more energy - from five to 17 times more electricity compared with treating rainwater.

Treating used water also produces sludge, which is then landfilled.

PUB said meeting future water demand with today's technology will see its electricity use go up four times to 4,000 GWh a year. The sludge waste produced will double to 600,000 tonnes a year by 2060.

In a statement last week, the PUB said this is unsustainable and can be overcome only through technological innovations.

And so, since 2002, together with research partners and the National Research Foundation, PUB has invested $453 million in over 600 water research and development projects. Its partners span 27 countries. These projects aim to increase future water resources and improve the efficiency of water treatment processes and operations.

STILL A STRATEGIC ISSUE

Despite how far Singapore has come in diversifying its water sources, political leaders here still consider it an existential issue for the country.

Academics studying water policy say the Republic's water strategy is way ahead of those in many countries with similar challenges.

Dr Cecilia Tortajada, senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy's Institute of Water Policy, said that while many countries have reservoirs or big bodies of water to draw from, these are often polluted, whereas Singapore's are clean.

Last month, local academics from the Institute of Water Policy and the National University of Singapore's geography department published a paper in science journal Environmental Research Letters, analysing the drought vulnerability of Singapore and Malaysia.

The paper said Singapore has adapted well to periods of drought, even supplying water to Malaysia during a regional dry spell, and was thus less vulnerable than Johor.

Still, comments on water from leaders across the Causeway recently have underlined some of the vulnerabilities that leaders in Singapore have been trying to hint at.

"If Malaysia cuts our water supply, there will immediately be a serious crisis in Singapore," said Dr Bilveer Singh of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, who said water remains an existential issue, despite Newater and other advances.

Commenting on the recent remarks from Malaysia, Dr Tortajada noted that the cost of water outlined in the 1962 water agreement goes both ways and benefits both parties.

Singapore pays three sen per 1,000 gallons of raw water, and sells treated water back to Johor at 50 sen per 1,000 gallons.

Fifty sen is a fraction of the true cost to Singapore of treating the water, which includes building and maintaining the entire infrastructure of water purification plants, said the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

It costs Singapore RM2.40 to treat every 1,000 gallons of water. By selling it to Malaysia at 50 sen, Singapore is providing a subsidy of RM1.90 per 1,000 gallons.

Having bought treated water, Johor then sells it to its people at RM3.95 per 1,000 gallons, earning a profit of RM3.45 per 1,000 gallons, or RM46 million a year.

Malaysia is also getting more water than provided for in the treaty.

Johor is entitled to buy up to five million gallons of treated water a day, but it has regularly bought up to 16 million gallons a day.

Dr Singh likens Malaysia's recent comments to that of a "big brother pushing a smaller one and trying to put him in his place".

ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute fellow Norshahril Saat added: "Dr Mahathir has shown he is committed to reforms in the domestic sphere but when it comes to foreign policy, it seems he has not changed."

Older commentators recall how bilateral relations between the countries went through a fraught period during Dr Mahathir's previous term as PM, when water prices became part of a so-called "package" of issues which were meant to be settled together, but were left largely unresolved when he stepped down.

MANAGING DEMAND IS KEY

Water expert Asit Biswas, distinguished visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and Stockholm Water Prize winner, believes that Singapore could provide for its own water needs, but the main challenge would be managing demand.

"This aspect, unfortunately, is not receiving enough attention," said Professor Biswas.

A water price hike here, the second phase of which kicked in last Sunday, was a step in the right direction. But other than pricing, Singapore should look to cities like Sao Paulo in Brazil, he said, and consider incentives for saving water, fines for excessive use and instilling a strong water conservation ethos in its people.

Each person in Singapore used about 143 litres a day last year - much more than the 75 litres a person needs to lead a "healthy and productive life", which is a finding from an earlier study, he noted.

Singapore's target is for per capita water use to hit 147 litres by 2020 - a goal that was attained early. Prof Biswas believes a more ambitious target of 100 litres should be set.

Another key area to monitor is industrial water demand, he added.

Singapore's water demand of 430 million gallons a day - or 782 Olympic-sized pools - is split between two sectors. The domestic sector uses 45 per cent, and the industrial sector 55 per cent.

But demand will double by 2060, with industries accounting for 70 per cent of demand by then.

In view of these numbers, Singapore should consider significant demand management practices for the domestic and industrial sectors, said Prof Biswas.

Some big firms such as Nestle and Unilever have reduced the water required to manufacture one tonne of product by between 40 and 45 per cent over the past decade.

They expect to reduce it by another 30 per cent by 2030, he said.

"With the appropriate policies, it is possible to contain total water requirements to about 20 per cent more than at present by 2060," he added.

In response to queries from The Sunday Times, a spokesman for the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources said it will continue to encourage households to use water more efficiently, such as through technology.

A field trial of smart shower devices showed that access to real-time data on water usage can motivate users to adjust their habits.

"PUB is now working with HDB to install these smart shower devices in 10,000 new homes as a pilot programme," it said.

PUB has also been stepping up efforts to manage industrial water usage, such as through the mandatory water efficiency management plan.

This plan helps heavy consumers of water to better understand their usage patterns, so they can assess how to better manage and optimise their water usage.