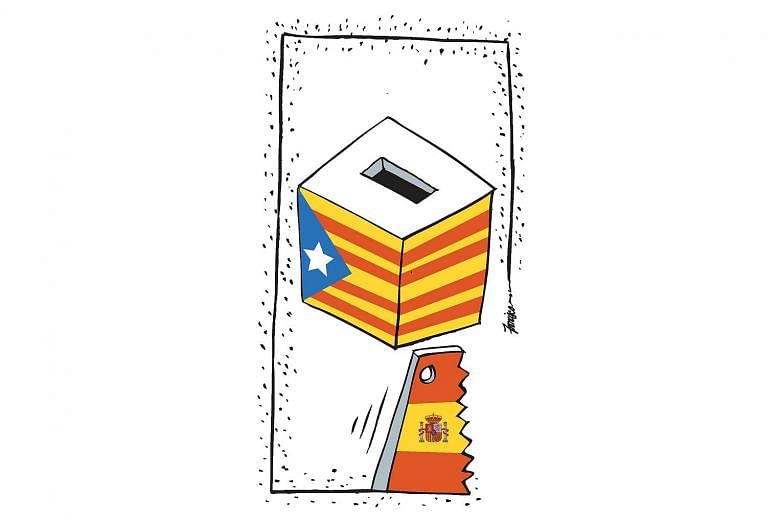

LONDON • The outcome of Spain's constitutional crisis remains unpredictable; Mr Carles Puigdemont, the leader of the separatists in Catalonia, has until tomorrow, when he faces his regional Parliament, to decide whether to make a unilateral declaration of his province's secession from Spain - risking further violence - or to draw back from the precipice, and settle for a more prolonged political confrontation with Spain's central government.

But at least in one respect, the extraordinary turn of events in Spain does highlight a broader and potentially dangerous development: the increasingly widespread use of popular referendums as a mechanism to legitimise and enforce a variety of narrow political demands.

Referendums used to be quite rare events; throughout the second half of the 20th century, only an average of 10 a year took place around the world. Recently, however, their number has increased fivefold.

Those who propose or hold referendums hail them as the highest form of democracy, an opportunity for every ordinary citizen to have a direct stake in making a decision. But far from being democratic, referendums often offer only the semblance of popular consultation, with none of the substance. And their increased use today is not a sign of strength but an indication of political weakness, another manifestation of the populist, anti-establishment backlash which is now buffeting many Western nations.

The first recorded example of what we'd recognise as a referendum comes from Switzerland in the 13th century. The Swiss continue to this day to be the biggest supporters of the procedure, holding about 190 referendums in the last 20 years alone.

But referendums were used by a variety of strongmen through history as a justification to overthrow the existing constitutional order.

France's Napoleon Bonaparte loved referendums; his brother organised one in 1800 to change the existing republican Constitution, and Napoleon had himself declared emperor in another referendum in 1804.

Adolf Hitler also loved referendums: He organised no fewer than four during his first five years in power - all intended to justify his position as a warlord and chief murderer. And needless to say, in all the referendums listed above, those voting "oui" or "ja" exceeded 90 per cent.

The suspicion that referendums lead only to mob rule is the main reason behind the establishment of parliamentary systems such as those which operate in the United States, most of Europe and countries such as Singapore; electorates vote periodically for their representatives, but it's up to these representatives - rather than the public at large - to take decisions on behalf of the voters.

Referendums, as Britain's post-war prime minister Clement Attlee once remarked, are "a device of dictators and demagogues".

That does not mean that they have no place whatsoever; most Constitutions make some provision for the possibility of referendums, albeit only in exceptional cases: In Germany, for instance, national referendums can take place only if there is a major constitutional change, while in Singapore, a referendum is envisaged only in the unique circumstances of either a severe legislative impasse between Parliament and president, or in case of a "surrender or transfer, either wholly or in part, of the sovereignty of the Republic of Singapore as an independent nation".

And even in countries like Switzerland where referendums are the norm rather than the exception, good governance is not necessarily the outcome. Switzerland did not grant its women the right to vote until 1971, mainly because its male electorate repeatedly voted this down. And the last canton (component unit) of the Swiss federation bowed to pressure to allow women the right to vote only in 1991. Switzerland has also been the originator of some strange "innovations" such as a legal ban on the construction of mosque minarets.

REDUCTIVE ASPECT OF REFERENDUMS

But quite apart from the objections in principle to referendums, there are also some very practical difficulties with the concept. The first relates to the question put to the vote in a referendum; it tends to reduce highly complex matters to a binary "yes" or "no" answer.

Last year, the people of Britain were asked to vote on whether their country should stay a member of the European Union, a highly complex question involving no fewer than 12,000 different pieces of legislation and legal obligations, touching every sphere of their lives. They voted to leave, and are now discovering what their vote actually means; the question was simply too complex to be put to the vote in such a cavalier, irresponsible manner.

There are also major difficulties with agreeing which majority should be considered decisive in a referendum. Is it really acceptable that the momentous British decision to leave the EU was taken last year by only 51.9 per cent of the ballots, on a turnout which was only 72 per cent of those entitled to vote?

It's not for nothing that some jurisdictions require a super majority in a referendum before change is effected, such as two-thirds of those voting, rather than a simple majority of 50 per cent plus one.

In Singapore, a referendum on surrendering any of the sovereignty of Singapore would be considered valid only if two-thirds of those voting agreed, and that provision in Singapore's Constitution can itself only be amended in a separate referendum in which two-thirds of the voters approved of a constitutional change, the sort of extraordinary "double-lock" safeguard designed to prevent precisely the situation in Britain, where a handful of votes changed the country's history with almost no debate.

An even bigger question is about who should be allowed to vote in referendums. That proved crucial in the case of Catalonia last week; Catalan separatists claimed that only the residents of Catalonia should vote.

But representatives for Spain's remaining 42 million people claimed, with some justification, that they should also have a say over their country's future.

More importantly, referendums do not settle contentious issues. For instance, Britain's departure from the European Union is now heavily contested.

Scottish nationalists are demanding a second referendum, to avenge their defeat in the first. The French voted in a referendum against the European Constitution, but got it nevertheless through the back door. The Dutch voted in a referendum last year against a free trade agreement with Ukraine, but that is now operating. And in Canada's Quebec province, two independence referendums had to fail before the issue was put in abeyance.

So, given all these difficulties, why are referendums still increasing in number? Largely because elected politicians lack the courage to take serious and contentious decisions, and so prefer to kick them back to the electorate, as Britain's then prime minister David Cameron had done last year with the EU issue.

But also because electorates in the electronic age actually value instant decisions; they are now increasingly equating their political involvement with something similar to tweeting or providing comments or instant feedback on social media websites.

Electorates are becoming more individualistic and are "moving away from the package deal" of old parliamentary constitutional arrangements, argues Professor Matt Qvortrup, who teaches applied political science at Britain's Coventry University and wrote a seminal study on referendums. "We expect to be able to compile our own playlists, in politics too," he explains.

THE PROBLEM WITH CATALONIA'S REFERENDUM

The trend towards more referendums may, therefore, be unstoppable. But that does not mean that anyone should accept what has happened in Spain's Catalonia. For the vote there was a sham which does not even deserve the name of a referendum. There were no electoral rolls, and no checks on who voted and why. There was no electoral commission, and no campaign. And voters were encouraged to print their ballot papers at home; the more papers they printed, the merrier.

Nor do the separatists represent a majority; in the regional elections held in 2015 they fell short of a majority, and have pushed their sham referendum precisely because they can't get what they want in any other legal way.

And finally, there are plenty of historic examples where even well-organised referendums were rejected by central governments with no consequence to the country's future unity. The US, for instance, rejected the independence referendums held in Texas, Tennessee and Virginia in 1861 as illegal. And Denmark rejected an independence vote in its Faroe Islands in 1946; the islands then turfed out their separatists, and are still part of Denmark to this day.

It behoves Spain and all its friends and allies around the world to stand firm over the crisis in Catalonia. Not because the Catalan aren't a nation; they are, and their rights are recognised and respected. Not because the Catalans can't have their say; they vote freely, for every assembly and council looking after their affairs. Not because they should never be independent; if that's what they and the rest of Spain decide, it's not up to anyone else to object.

But because what passed for a referendum in Catalonia last week must not be allowed to stand, since it is the negation of constitutional government. And because the entire trend of more referendums is corrosive to current international order.