The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) - the biggest trade deal in history - has got a new lease of life. But it remains limited in its geographical coverage - something that can be substantially remedied if China and India also sign up.

With the addition of the two Asian giants, it would then cover countries with a total population of about three billion instead of 500 million, and a combined gross domestic product of US$25 trillion (S$34 trillion) instead of US$13 trillion.

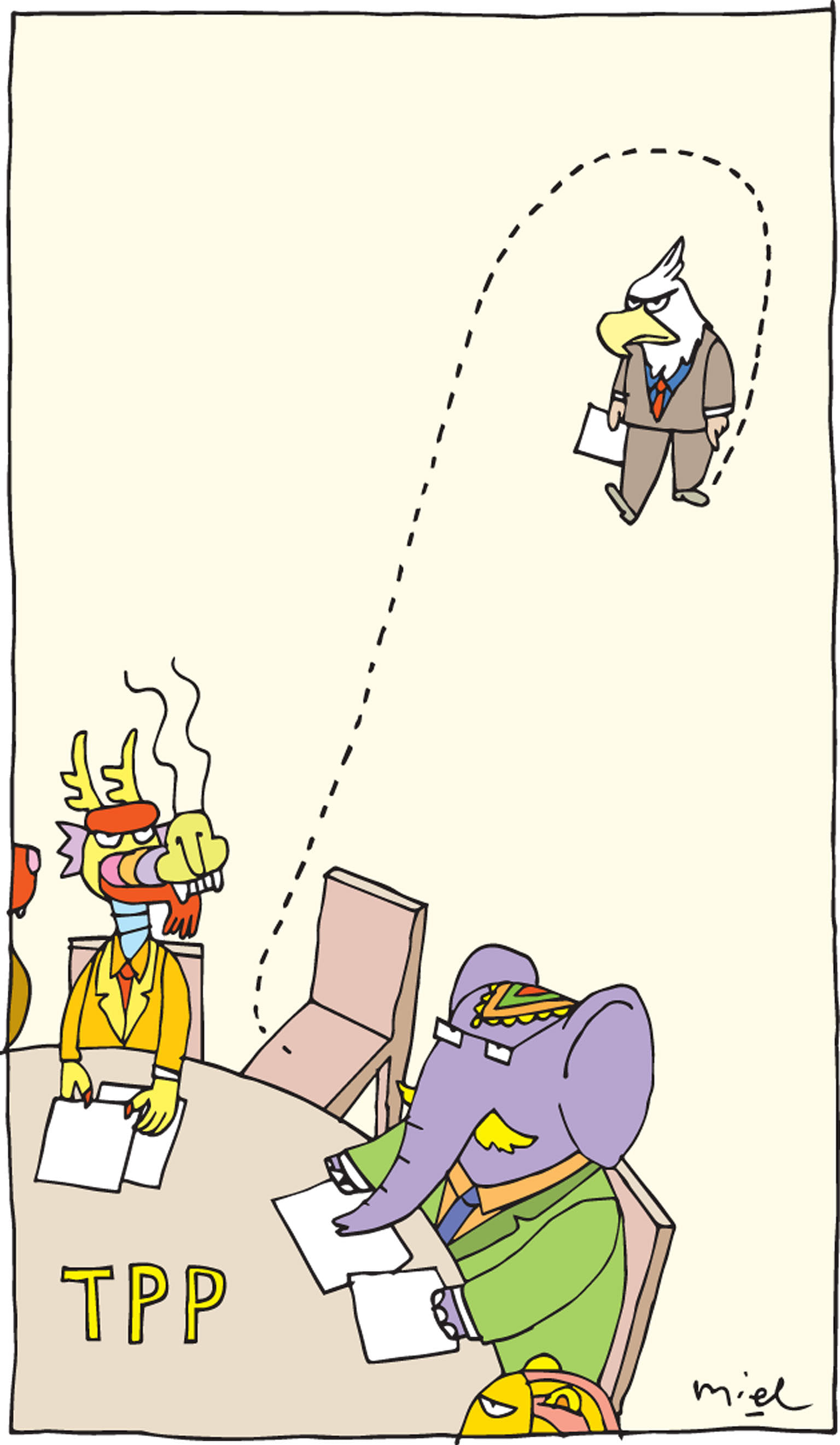

After US President Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the TPP on his first day in office in January, many observers pronounced the agreement to be all but dead. But thanks to the persistence of the remaining 11 members, led by Japan, it has been formally resurrected following the meeting of the leaders of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in Vietnam over the weekend. However, there are three glaring omissions in the composition of its membership: the US, China and India.

Under the Trump administration at least, there is little chance of the US coming back on board. Mr Trump has repeatedly excoriated the TPP as being a job-killer at home and it would be hard for him to backtrack. But China and India, both of which were excluded, should now seriously explore signing up.

The TPP, which was originally mooted by the Obama administration as part of its "pivot to Asia" strategy, was partly intended to limit the dominant influence of China in setting the rules and agenda for trade in the region. But geopolitical rivalry aside, when it came to trade, excluding China made little sense, given that it was the largest trading partner of almost all the members of the TPP. Excluding India, one of Asia's fastest-growing economies and its third largest, was also an anomaly.

Having been excluded, China and India stand to lose out from the TPP. They will face higher tariffs in TPP member economies than would the TPP members when they trade with each other. China and (especially) India would also lose in the area of services as well as inward foreign investment, where TPP members will be more committed to protecting the rights of investors.

TPP members would in turn face high tariffs on certain goods, including farm products, when they sell to the huge markets of China and India. They would also be subject to non-tariff barriers that would be far less if China and India were part of the TPP. Including China and India in the deal would, in net terms, be a win-win for all concerned.

China's response to its exclusion from TPP has been to accelerate other agreements to which it is a party, notably the 16-country Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which also includes India - although this has moved slower than the TPP.

However, as a trade agreement, the TPP is superior to the RCEP. The TPP covers more goods, with almost every tariff line falling to zero, which would especially benefit China. It also covers more services, which would especially benefit India, whereas the RCEP covers a limited list.

In addition, the TPP is more pro-investment, offering stronger protection for investors and it mandates higher environmental and labour standards. It also has better provisions for intellectual property protection - although many of these have been suspended (though not scrapped) in the latest version of the TPP.

To be sure, China and India have so far not been enthusiastic about joining the TPP - even though theoretically, they would be permitted to do so - it is a party they would not like to attend, even though they have not been invited.

The standards set by the agreement would require both to make major reforms such as an overhaul of the way their state-owned enterprises work, the dismantling of several non-tariff barriers, the opening up of their service sectors as well as government procurement to foreign firms, and the dismantling of restrictions on e-commerce that favour local firms.

But China and India have a record of pushing through bold reforms, especially under their current political leaders, both of whom enjoy strong popular support.

They would have to pursue such reforms sooner or later anyway - or else they stand to lose their competitive edge vis-a-vis their TPP-member trading partners.

Besides, if a less developed economy like Vietnam can commit to the provisions of the TPP, China and India can surely make the grade.

Finally, what of the US? Having frozen itself out of the TPP for the moment, it is talking of other architectures like the Indo-Pacific Partnership (IPP) - which is so far undefined, but said to include India, Japan and Australia, besides the US.

But the Trump administration has indicated it is more interested in bilateral deals than multinational arrangements. So an IPP, if it happens, is likely to take a while and be, again, limited in scope. To many observers, it looks suspiciously like another construct designed to "contain" the influence of China, a bad formula for a trade agreement, which should be about trade, not geopolitical one-upmanship.

Meanwhile, the TPP, which has been rechristened the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, is going ahead and will likely take effect in 2019. Many other countries, including South Korea, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, have also expressed interest in signing up.

Once China and India join, or even if they indicate an intention to do so, the US will have a hard time justifying to itself why it is staying out. It will face pressure from US companies, which will find themselves at a disadvantage vis-a-vis firms from TPP members when operating in Asia.

Eventually, the US will be compelled to return to the TPP. If not the Trump administration, then its successor will quite likely bring it back in. This could happen as easily as Mr Trump took it out, with the stroke of a pen.