Dear Yuen Sin,

When I was 22, I travelled overseas alone for the first time. It was the year 2010, and Shanghai was holding the World Expo. I can still vividly remember being stuck in those much-documented vast queues of that expo, and consider that to be my first encounter with contemporary China.

That summer trip also broke the stereotypes that I had of the country.

For example, I remember reading reports about how Chinese nationals visiting the expo were behaving in an "uncivilised" way. Some netizens criticised the unseemly rush by some into the pavilions to get stamps on their passports.

But though I had witnessed the same scenes described in the media, something else left a deeper impression on me. I realised that these visitors at the expo were from different parts of China and, like me, they were in Shanghai to get a glimpse of what was considered to be a condensed version of the best of the world, and to understand the modern China they found themselves now in.

During that visit, I realised that a fast-progressing China was facing its own set of challenges.

I have since travelled to many Chinese cities, and now know China to be a place that is complex and multi-faceted. On a trip to the Xilamuren Grassland in Inner Mongolia, my friends and I sat around a campfire outside a yurt, and we sang at the top of our voices. In the Kubuqi Desert, we played desert volleyball with friends on the same tour.

Recently, I went to Chongqing to visit a colleague but, instead of heading for the popular hotpots, we went to a Japanese izakaya for dinner, and had skewered meat with beer. In Chengdu, I communicated with my Airbnb host on WeChat - the popular Chinese social media platform - and we talked about our favourite authors such as Yang Jiang and Haruki Murakami. We had somehow established some kind of friendship on a virtual platform.

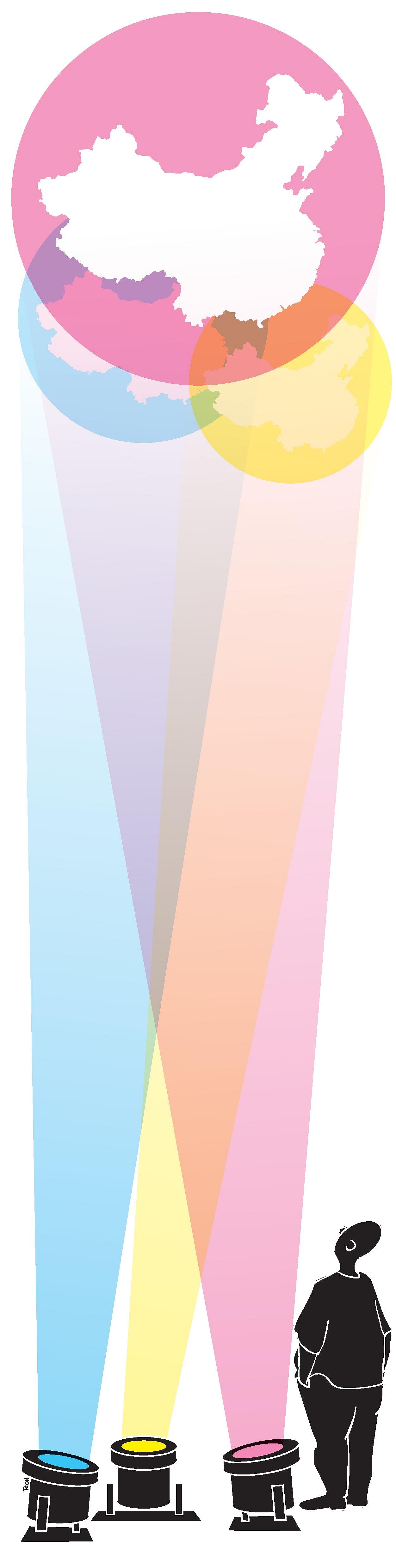

All these different experiences seem to demonstrate that, with modernisation and the opening up of China, the country is also capable of replicating the same experiences that other cities can provide. Globalisation has truly made the world flatter.

As a Chinese Singaporean, I also sense that there is a delicate complexity to how we perceive China from the outside.

At a talk titled "Understanding China: The 19th Party Congress" held at the National Library last month, Lianhe Zaobao associate editor and zaobao.com editor Han Yong Hong made a similar point.

While China's soft-power charm offensive has caused some Singaporeans to hope for closer bilateral ties between the two countries, others, amid a growing sense of national identity, feel that relations should be kept as those between friendly states but without the common ethnic element coming into the picture.

She pointed out that these two different views may cause tension between the local Chinese and non-Chinese communities.

It may be that the rise of China has not noticeably changed the predominantly English-speaking language environment in Singapore, but academics, at least, have been wary of the possibility of a resinicisation of the Chinese in the region and how that might strengthen the identity of the ethnic Chinese in South-east Asia.

Some also think that for a multiracial country like Singapore, the growth of China's influence has to be observed with caution.

I am, however, optimistic that Chinese Singaporeans are able to view the changes in China through a rational lens.

For example, you might have seen how many in Singapore rooted for local singers Nathan Hartono and Joanna Dong when they participated in Sing! China. It wasn't just a matter of thinking that China had become cool.

Even though people accepted that China was providing Singaporeans - citizens from a small country - with a big stage to shine, they were at the same time aware that the game had its own rules. Some local netizens commented that the Singaporean contestants would already be "winners in their own right" even if they finished second. It was a kind of "alternative affirmation", since many knew it was impossible for a Singaporean to emerge as champion in Chinese competitions like these.

Singaporeans are realistic in assessing the impact of a rising China. At the same time, Hartono's "English-speaking" identity, Dong's bilingual capabilities and their choosing to perform Western jazzy numbers instead of the usual Chinese songs heard on the show, probably also made it easier for Singaporeans to identify with them.

Also, while it might be true that some Singaporeans feel a certain "closeness" when visiting Chinese cities, my view is that it might more likely be due to the fact that people there are now very much like their counterparts in the West in terms of values and living habits. With the tides of modernisation come the effect of cultural homogenisation.

For Singaporeans who venture to China, they see a land of opportunity. There is less of that poetic imagination of the past, and more pragmatism.

On the other hand, a stronger Singaporean Chinese cultural identity seems to have emerged in the past few years. Traditional art forms that originated from China, like Nanyin music and Teochew opera, have developed and been given a new lease of life here.

When I visit China now, I am confident that the sense of ease I feel walking on its streets does not originate from any form of abstract cultural identity.

Instead, it is more due to the fact that I am bilingual. I am able to code-switch when I need to, and can sometimes even imitate the accents of the locals and try to blend in.

This sense of comfort will also not affect my objectivity when it comes to China. Unlike older generations of Chinese Singaporeans who might regard China as "closer to home", I feel no emotional conflict when asked about my views on China. It is easy to stand firm in my identity as a Singaporean, and evaluate China with an open-minded attitude at the same time.

Wai Mun

(Translated by Lim Ruey Yan)

Is China now more hip than Singapore?

Dear Wai Mun,

On the first day of Secondary 2, my Chinese teacher appointed me the Chinese subject representative after just a mere glance at the class register.

The reason? My name, comprising two words including my surname, branded me as being more "Chinese" than the rest of my peers. After all, such names are more common in China, and hark back to ancient Chinese poets like Du Fu or Li Bai, not Chinese Singaporean names which tend to either come with a Western name like Cheryl or comprise three words like Lim Xin Yi.

Whenever the dreaded response to my name - "Are you from China?" - came about when I met someone new, it would spark a vehement denial.

Yes, my parents are Chinese-educated, but they were born in Singapore, I'd emphasise. In fact, one reason they gave me such a short name was quintessentially Singaporean - to save me time in exams.

I turn 26 this year, but unlike you, Wai Mun, I grew up with a sense of awkwardness and discomfort with the idea of China. As a teenager, never once did I view an association with China as something that would boost my social capital among my westernised Singaporean peers.

In fact, while I have traversed the world, visiting countries from Morocco to Montenegro, I have never once stepped into China - the home of my grandparents.

Even as my mother - the only one among three siblings born on Singapore soil - spoke highly of China's rise, the impression I got of it was that of a developing country, stymied by a population that was lacking in social graces despite its eagerness to flaunt its new wealth.

As someone comfortable speaking Mandarin with my closer friends, I was aware there were circles of people who looked down on those like me. English seemed to be the language that cosmopolitans excelled in to get ahead in the working world, while Mandarin was the dominant language of the heartland.

In the self-conscious hierarchy of identities that I had assembled in my adolescent mind, embracing my Chinese Singaporean roots was already an act that placed me on a lower footing compared to those who consciously disavowed their Chineseness from the outset. Why exacerbate it by tracing links to a country that not many hold in high esteem?

As a result, the greater the sense of pride I took in my ethnic identity, the more China felt like a looming spectre to be held at arm's length.

Some time between 2010 and 2017, the cultural tables slowly turned. While I spent my undergraduate years in Britain, other friends - especially the ones who resisted speaking in Mandarin even during mother tongue classes - started travelling to Shanghai or Beijing for internships or study programmes, and spoke breathlessly of their experiences.

The words "Alibaba", "Taobao" and "Jack Ma" crept into the mainstream consciousness in Singapore, and even the Western media started paying more attention to Chinese actresses like Zhang Ziyi and Tang Wei and supermodel Liu Wen as China's soft power began to gain traction.

Speaking well of China no longer felt uncool, now that more people have come out to admit that it may even be trendier than us cosmopolitan Singaporeans. Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say said he felt like a "suaku" (country bumpkin) on a trip to Shanghai a few years ago, when he paid in cash at a roadside hawker stall while other customers simply used WeChat Pay on their phones.

There was a similar effect when the Mandarin-spurning Anglo-Chinese School boy Nathan Hartono competed in Sing! China in 2016, reversing years of rejecting his mother tongue with this prodigal return to his Chinese roots.

This recent change in perspectives may well be purely instrumental - done for economic gain as China grows richer, for example - and may also be brought about by the technological development and modernisation of Chinese society, as you have pointed out.

But at a personal level, it served as a catalyst for me. A sense of assurance and affirmation came from a group in the mainstream that said it was okay to embrace "Chineseness" - be that of the China or a Singaporean variety.

Even though I was late to the game when it came to uncovering the nuances and idiosyncrasies of a modernising China, and began picking up books and watching documentaries on China only when I was in university, it felt like a case of better late than never.

Reading about issues of class and migration in journalist Leslie T. Chang's book, Factory Girls, and Lixin Fan's documentary, Last Train Home, opened my eyes to the stark complexities of life in the flux of modern China, and to the sheer diversity of the different groups of people in this huge nation.

At the same time, they stirred a sense of curiosity about my own roots, and prompted me to turn to translated copies of books by Chinese Singaporean writers like Yeng Pway Ngon, which told of historical developments closer to home with a distinctly local consciousness.

While some people might think that embracing Chinese culture entails a different kind of cultural colonisation of Singaporeans by a rising superpower, I feel that Singapore has, after 53 years of independence, developed a unique DNA that would make it very difficult for us to be co-opted by any other regional power.

After all, some Chinese Singaporeans even think of Chinese nationals as being of a different race. This was pointed out by National Institute of Education lecturer Yang Peidong in a 2013 essay, when he noted how some Chinese Singaporeans call out prejudice against Chinese nationals as "racism". It shows how distinct and distant new generations of Chinese Singaporeans have come to think of themselves as opposed to those from China, he said.

These days, I no longer feel self-conscious about my name. The character "Xin" means dawn, or the morning light, and there is something about the spareness of my two-worded name that I find rather beautiful. I will choose to have a unique name like this over being mixed up with thousands of other Cheryls and Andreas on this island any day.

Perhaps it could even earn me some social capital when I finally visit China one day.

Yuen Sin

TOMORROW: THE ISSUE OF "CHINESE PRIVILEGE"