UNITED STATES (NYTIMES) - Tim Cook was angry.

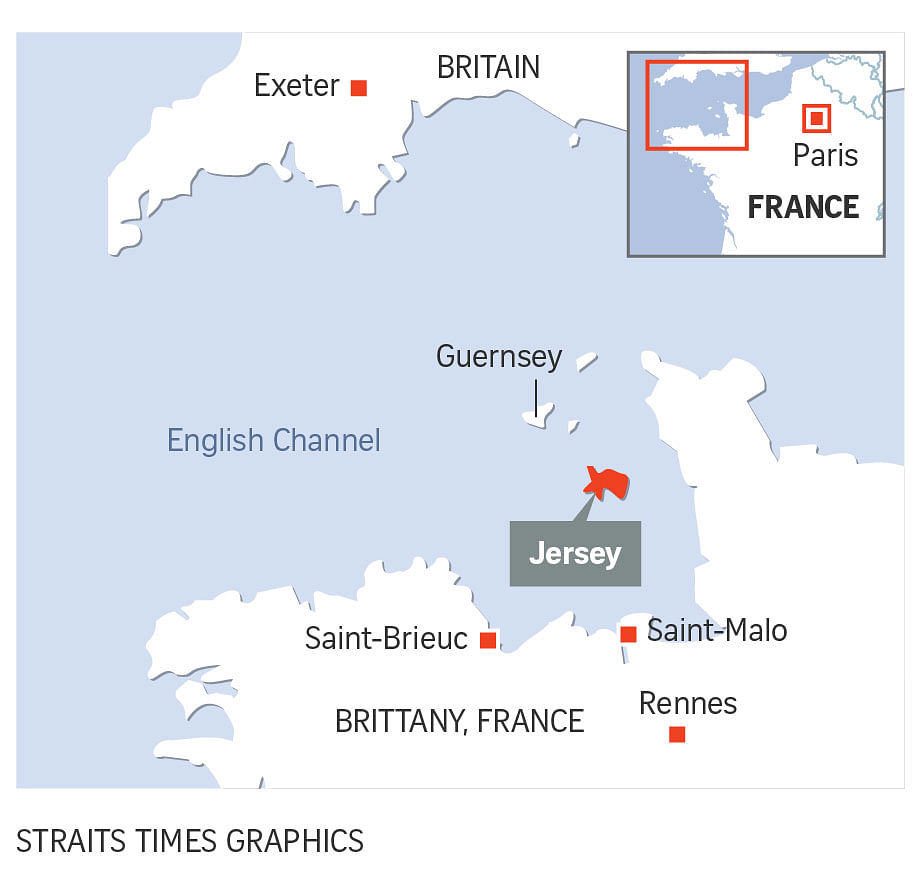

It was May 2013, and Mr Cook, the chief executive of Apple, appeared before a US Senate investigative subcommittee. After a lengthy inquiry, it found that the company had avoided tens of billionsof dollars in taxes by shifting profits into Irish subsidiaries that the panel's chairman called "ghost companies". "We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar," Mr Cook declared at the hearing. "We don't depend on tax gimmicks," he went on. "We don't stash money on some Caribbean island." True enough. The island Apple would soon rely on was in the English Channel.

Five months after Mr Cook's testimony, Irish officials began to crack down on the tax structure Apple had exploited. So the iPhone maker went hunting for another place to park its profits, newly leaked records show. With help from law firms that specialise in offshore tax shelters, the company canvassed multiple jurisdictions before settling on the small island of Jersey, which typically does not tax corporate income.

Apple has accumulated more than $128 billion (S$ 174 billion) in profits offshore, and probably much more, that is untaxed by the United States and hardly touched by any other country. Nearly all of that was generated over the past decade.

The previously undisclosed story of Apple's search for a new island tax haven and its use of Jersey is among the revelations emerging from a cache of secret corporate records from Appleby, a Bermuda-based law firm that caters to businesses and the wealthy elite.

The records, shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists with The New York Times and other media partners, were obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.

The documents reveal how big law firms help clients weave their way through the gaps between different countries' tax rules. Appleby clients have transferred trademarks, patent rights and other valuable intangible assets into offshore shell companies, avoiding billions of dollars in taxes. The rights to Nike's Swoosh trademark, Uber's taxi-hailing app, Allergan's Botox patents and Facebook's social media technology have all resided in shell companies that listed as their headquarters Appleby offices in Bermuda and Grand Cayman, the records show.

"US multinational firms are the global grandmasters of tax avoidance schemes that deplete not just US tax collection but the tax collection of most every large economy in the world," said Professor Edward Kleinbard, a former corporate tax adviser to such companies, now a law professor at the University of Southern California.

Indeed, tax strategies like the ones used by Apple - as well as Amazon, Google, Starbucks and others - cost governments around the world as much as $240 billion a year in lost revenue, according to a 2015 estimate by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The group is overseeing efforts to change the global rules that permit such maneuvers.

The disclosures come on the heels of last week's proposals by Republican lawmakers to provide several new tax benefits for multinational companies, including cutting the federal corporate income tax rate to 20 per cent from 35 per cent. President Donald Trump has said US businesses are getting a bad deal under current rules.

But the documents show how major US companies find creative ways to avoid paying anything close to 35 per cent.

Apple, for example, pays taxes at a small fraction of that rate on its offshore profits, according to calculations by The Times based on the company's securities filings. Apple reports that nearly 70 per cent of its worldwide profits are earned offshore.

An Apple spokesman, Mr Josh Rosenstock, declined to answer most questions about the company's tax strategy. He did say that Apple had told regulators - in the United States and Ireland and at the European Commission - about the reorganisation of its Irish subsidiaries. "The changes we made did not reduce our tax payments in any country," he said.

Allergan, Facebook, Nike and Uber said they complied with tax regulations around the world, according to prepared statements.

Congressional Republicans are also seeking to impose a 10 per cent tax on some of the profits that US businesses say are earned offshore - half the rate they are proposing for profits in the United States. The lawmakers have also proposed another break, permitting multinationals to bring home more than $2.6 trillion stowed offshore at sharply reduced tax rates. Both proposals, critics say, would only create additional incentives for businesses like Apple to shift more profits into island hideaways.

Tax authorities have challenged several of the offshore structures maintained by Appleby and Estera, a spinoff of the law firm's corporate services business. Nike triumphed over the Internal Revenue Service in a fight over back taxes a year ago; a similar dispute between the IRS and Facebook is continuing.

European regulators are trying to force countries including Ireland, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands to collect back taxes from big companies that relied on offshore arrangements.

Apple's hunt for a tax haven is a familiar tale, said Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah, director of the international tax program at the University of Michigan Law School, who also reviewed the Appleby documents.

"This is how it usually works: You close one tax shelter, and something else opens up," he said. "It just goes on endlessly."