The Asian Voice

What's cooking in Nepal-China relations?: Kathmandu Post contributor

The writer says that China has maintained an 'undeclared blockade-like situation' at Tatopani and Rasuwagadhi, to Nepal's detriment.

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

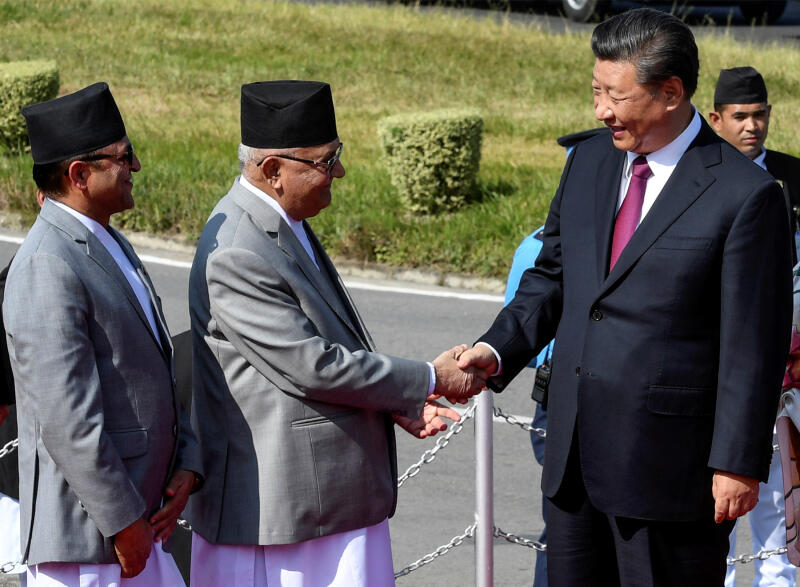

China's President Xi Jinping shaking hands with Nepal's Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli as he wraps up his two-day visit to Nepal, in Kathmandu on Oct 13, 2019.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Achyut Wagle

Follow topic:

KATHMANDU (THE KATHMANDU POST/ASIA NEWS NETWORK) - Last week, Minister for Industry, Commerce and Supplies Lekh Raj Bhatta in a public statement declared that the time had come to seriously reconsider whether Nepal should at all trade with China.

He was reacting to 'an undeclared blockade-like situation' enforced by China on imports of Chinese goods into Nepal. Trade across the land border has almost entirely stopped, right since the outbreak of Covid-19 a year ago.

It is perhaps for the first time in the seven decade-long Nepal-China diplomatic relations that any incumbent minister has lambasted China so openly for the latter's imperviousness to facilitate cross-border trade.

Incidentally, Mr Bhatta was expressing his displeasure over China in a function organised to mark the 24th anniversary of Nepal Intermodal Transport Development Board, an entity that manages about a dozen inland container depots and facilitates Nepal's foreign trade.

According to reports, China, on the pretext of containing the possible transmission of the novel coronavirus, is allowing only four to five truckloads of goods from each of the two key border points, Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani, to enter Nepal per day, which is only about five percent of normal cargo movement.

This has a proportionate impact on revenue collection. Rasuwagadhi Customs Office has collected about 15.4 per cent of its annual target of Rs 11.33 billion (S$210 million) while Tatopani Customs has collected only Rs 400 million out of the annual target of Rs 5.47 billion.

It is estimated that about US$200 million (S$266 million) worth of goods, in about 1,500 containers, imported by Nepali businessmen from or via China have been stranded across these two border points for the past year.

Nepali businessmen have suffered a huge loss due to damage and rotting of goods, particularly the perishable ones.

Although Nepali authorities unfailingly claim that they have communicated Nepal's concerns to Beijing, there have not been any changes on the ground.

Instead, last Saturday (Jan 30), the traders reportedly protested against the Chinese highhandedness, which was highlighted in Indian media; the information was, conspicuously, missing in the mainstream Nepali press.

Chinese goods constitute 15.4 per cent of Nepal's total import trade as against only 1.2 per cent of exports. In value, in the fiscal year 2019-20, Nepal exported goods worth only Rs 1.19 billion while importing about Rs 182 billion worth.

The direction of trade is heavily in the interest of China and the total share of Nepal's foreign trade with the northern neighbour has grown exponentially over the period of a decade, from little over 2 per cent.

Nepal's current trade bottlenecks with China come at a time when Nepal struggles to maintain a smooth supply of essential goods in the market, as well as an uninterrupted flow of machinery, equipment and materials for development projects, many of which are being developed by the Chinese contractors.

To recall, China has declined Nepal's request to fully operationalise the Tatopani border point that was closed right after the Gorkha earthquake in April 2015.

The focus then was shifted to open Rasuwagadhi customs point that still has far less convenient than Tatopani in terms of infrastructure connectivity like road, warehouse and other logistics.

Back then, the unofficially communicated Chinese 'security concern' was that the advocates of the Free Tibet movement used the Tatopani entry route 'posing threat to instability' in Tibet.

Whatsoever the reason may be, it affected imports from China, let alone exports from Nepal.

All these constraints have cropped up against the backdrop where Nepal has signed at least four trade and transit protocols with China and were thought to facilitate not only bilateral trade but also provide transit access to third countries.

The relations between the ruling Communist Party of China and the Nepal Communist Party headed by Oli, and between the two governments thereof, are claimed to have been the best in history.

China as the immediate and resourceful neighbour certainly is in a position to support Nepal at present on multiple fronts. But that goodwill is not forthcoming. On the contrary, China has not shown adequate sensitivity to resume normal trade.

The excuse given, of the 'containment of the virus', may appear plausible. But what would have been the predicament of import-dependent Nepal had India, in the same pretext of protecting its citizens from virus, imposed similar restrictions on trade and transit?

As China boasts of the global reach of its domestically developed Sinovac Covid-19 vaccines, including its professed willingness to donate to poorer nations, there is no indication of Nepal being included on that goodwill list in a meaningful way - for whatever reason.

China's cold-shouldered approach towards Nepal has lately found ground in a conspiracy that tries to establish the pandemic as just an excuse not to fully open the customs points.

The real motive is to express its displeasure, in the form of the 'undeclared blockade', against the split of the Nepal Communist Party - despite Beijing's insistence at presenting a united front.

Thus, the non-cooperation towards the Oli government is believed to have expanded way beyond trade issues. It is public knowledge that China is still keen to unite the Nepal Communist Party, whatever way possible.

All these conspiracy theories may or may not be entirely true. But the use of an economic blockade, hard or soft, as a weapon by both the disproportionately powerful neighbours to capitulate Nepali rulers in their political agenda is never a benign idea.

The Chinese economic blockade to Nepal is in fact a so far unheard of phenomenon in our modern history.

It might have also been due to the fact that economic and trade exchanges were very limited.

But when China emerges as the global superpower, its ambition of extending strategic influence, particularly in the neighbourhood, can only be fulfilled by magnanimity and good-faith; certainly not by a brute exhibition of might.

The writer is an econo-political analyst, writing for The Kathmandu Post for many years. The paper is a member of The Straits Times media partner Asia News Network, an alliance of 23 news media titles.