NEW DELHI/BANGALORE - It still hurts when Mr Balaram Nayak recalls how he endured the Indian government's poorly planned lockdown announced in March last year.

"Nobody was there to listen to us, neither from the government nor the police. Even the owner of the factory abandoned us," said the migrant who worked at a lace factory then in Surat in the western state of Gujarat.

Stranded more than 1,600km away from his home in Odisha's Ganjam district, Mr Nayak, 21, survived on money he borrowed from his family and others, as well as handouts from locals, before managing to get on a bus home in May last year.

He went hungry on certain days and even got beaten by the police once when he stepped out to buy vegetables.

Mr Nayak thought the worst was over and returned to Surat in November last year as the pandemic ebbed. But cases as well as deaths because of Covid-19 are flaring again in the city, where metal furnaces are melting at overworked crematoriums and several Odia workers have died recently.

Scared of contracting Covid-19 and apprehensive of a second lockdown in the city that is already under night curfew, he left for home on April 7.

His twin brother Krishna, who works at a snack factory in Jammu and Kashmir and had a similar horrifying lockdown experience, also returned home this month.

"We will see how we survive but we don't want to return until we get vaccinated," Mr Nayak added.

Many migrant workers such as the Nayaks are headed home again as India battles a vicious surge in cases, forcing many state governments to place night curfews and threaten lockdowns.

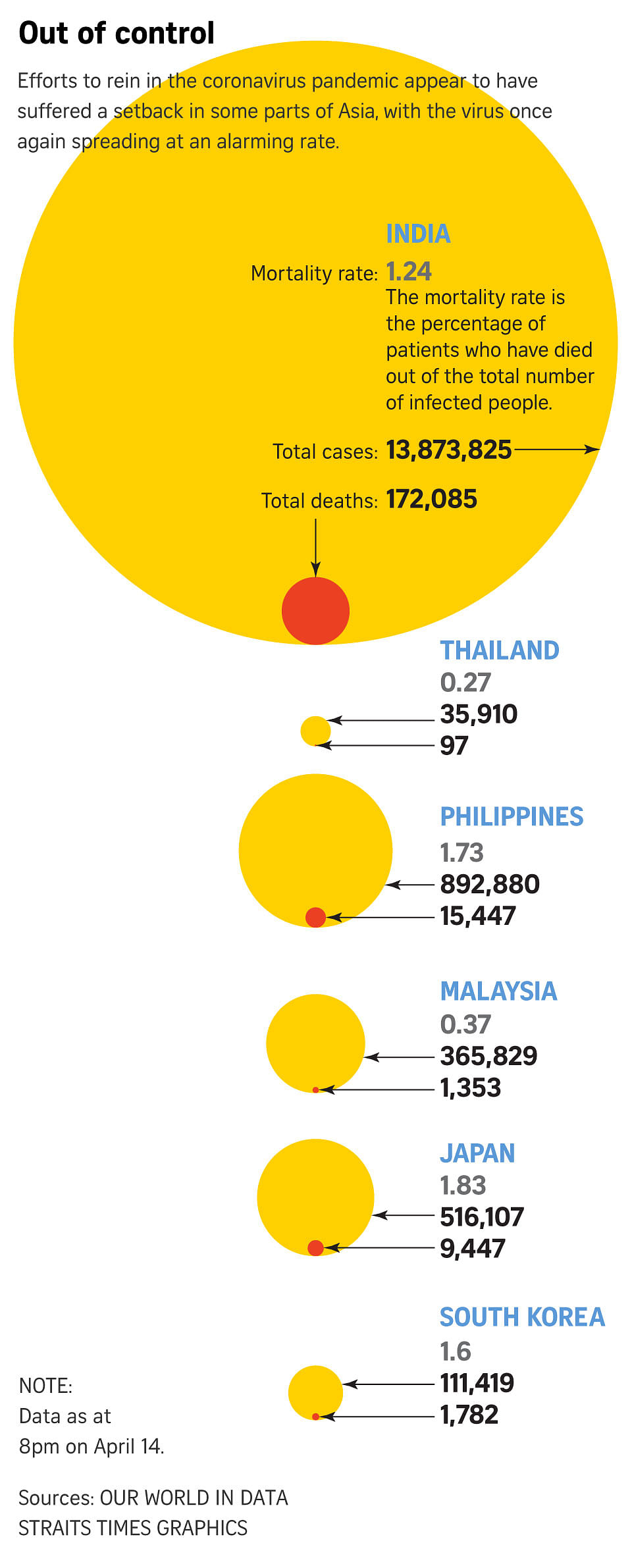

On Wednesday (April 14), the country reported 184,372 new coronavirus infections - its highest daily figure since the pandemic began - taking its tally past 13.8 million. This week, India overtook Brazil to become the world's second-worst affected country in the pandemic, following the United States.

Mr Sachin Chauhan, 21, was among those waiting for a bus on Tuesday at a roundabout in Greater Noida, a Delhi suburb. He cleans the glass front of a multi-storeyed office complex for a living, but chose to return home to Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh given the rising Covid-19 cases.

"It is better to be safe. We can earn as much as we want later," he said.

Night curfews, an effort to limit the spread of Covid-19 without crippling the economy, have, however, already impacted businesses such as restaurants.

"We need to serve the last customer at 9pm now (unlike 11pm before), an hour before the curfew begins, so that we can clean up inside," said Ms Ashwini G, the accountant at Aarogya Aahara, a South Indian fast food restaurant in Bangalore.

Their tables were all occupied on Tuesday evening, but an elderly customer wolfing down vadais, a savoury fried snack, noted that there was finally standing room in the otherwise overcrowded outlet.

Mr Gandhar Kumar, a waiter at a Punjabi restaurant said the Bangalore police had threatened them with a fine of 10,000 rupees (S$178) if they are found catering to large groups.

"We tell people to sit apart, but they don't listen. If we all follow social distancing rules, the government may not convert the night curfew into a full lockdown. No business outlet wants that," he said.

Even as people throng restaurants, markets, religious gatherings, parties and weddings, hospitals are filling up with Covid-19 patients.

This has revived nightmarish situations from last year when hospitals in many parts of the country had to ration medical oxygen as demand outstripped supply and families of Covid-19 patients struggled to find live-saving drugs such as remdesivir.

As at Wednesday morning, only 66 of Delhi's 1,177 ventilator-equipped beds were free.

The carelessness and "absence of fear of Covid unlike the first cycle in 2020" frustrates Dr Archana Prabhakar, a Bangalore-based family physician.

"I wish people would understand the seriousness of the situation," she said.

The doctor teleconsulting with dozens of Covid-19 patients who are recovering at home spent hours on Tuesday looking for an intensive care unit bed for a 91-year-old patient whose "oxygen saturation levels were dropping rapidly". She called 16 top private hospitals in the city. None had free beds.

"One of the hospital staff said that if someone passes away, there might be a bed for my patient," said Dr Prabhakar. After much effort, she managed to admit another patient, a 23-year-old, in a little-known nursing home with only one doctor.

But as migrants begin to head home, Mr Santosh Dalabehera, 32, is going against the tide.

The owner of a grocery store in Surat had returned home to Ganjam to be with his worried family. But Mr Dalabehera, who helped Odia migrant workers during the last lockdown in Surat, said he will head back to the city in a week's time. "People need my help," he said.