NAGOYA – Nineteen-year-old Sougo Ito counts himself first as a train otaku (geek), then a pop idol with nine-member Japanese boyband Super Dragon.

His Instagram profile picture, of him decked out in a train conductor outfit, bears this out. He devotes most of his social media presence to his passion for trains – both high-speed and local – rather than his pop star activities, and professes “sadness” at old trains being decommissioned.

“Since I was little, I have been going to Tokyo Station just to watch the shinkansen,” he said. “I fell in love with how it connects people together and bridges them with their hopes and dreams, by running every day and ferrying them to their destinations.”

Mr Ito’s observation encapsulates the relationship that many Japanese have with the six-decade-old shinkansen – literally “new main line” in Japanese but refers to the bullet train or high-speed rail (HSR) – as one that is more than just a means of transport.

It is a symbol of mobility – both for the millions of executives traversing the nation on business trips and the young Japanese who leave their homes as they come of age, to attend university or find work in the big city.

Nagoya-based delivery rider Yuma Takagi, 26, who grew up in the western city of Shimonoseki, makes an annual pilgrimage home via shinkansen at the year end, joining millions of others in what is a peak travel period in Japan.

“I’ve taken a domestic flight only once before, and that was for a high school excursion,” he said. He added that the shinkansen is also his preferred mode of travel when visiting friends in other cities.

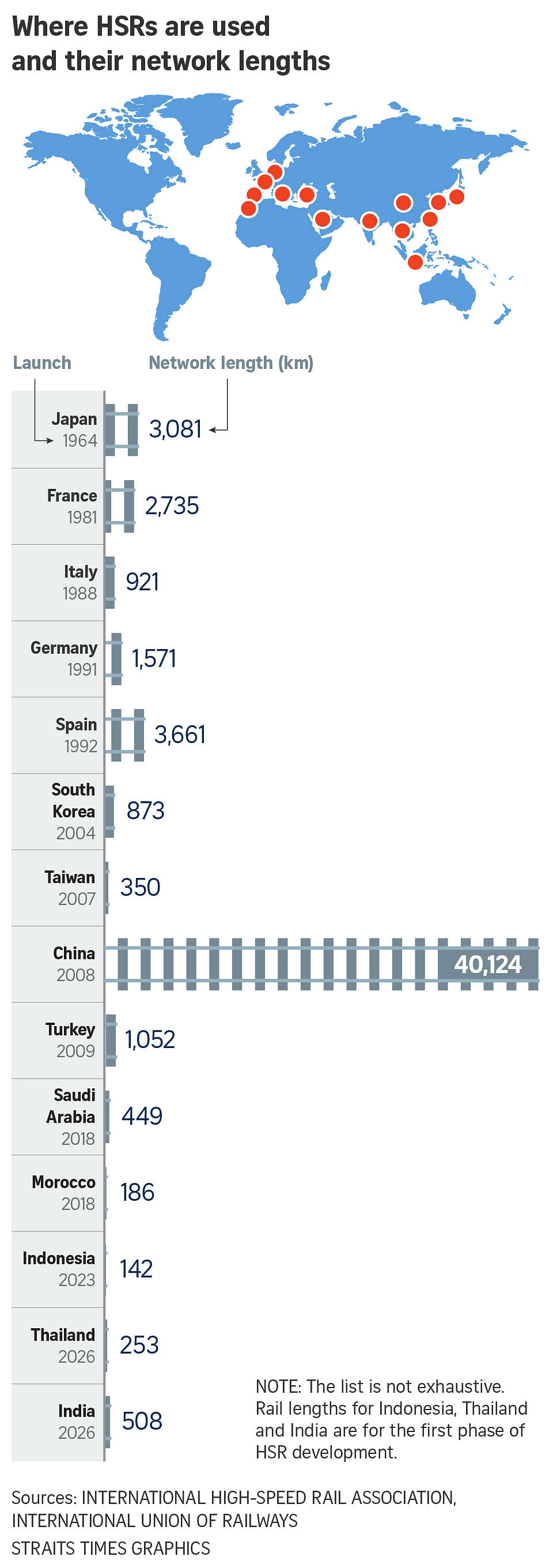

This year marks the 150th anniversary since Japan’s first railway line opened in 1872, connecting Shimbashi and Yokohama stations in the Greater Tokyo region.

Railways have evolved since then, from steam locomotives to electric trains and the shinkansen, which captivated the world when it began service on Oct 1, 1964, a week before the Olympic Games opened in Tokyo.

The shinkansen quickly became an icon for Japan as a pioneer in high-speed rail globally and has been featured in Hollywood films such as Inception (2010) and received top billing in the Brad Pitt-produced Bullet Train (2022).

Ridership on these superfast and ultra-efficient trains far outpaces domestic air traffic. Travelling by HSR removes the hassles usually associated with air travel: Train stations in the city are typically easier to get to than the airport, and there is no need to undergo security procedures. It also affords more flexibility, given the sheer volume of services plying a single route in a day.

In 2021, 195 million passengers travelled by HSR compared with 43.9 million by air, data from Statista shows. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, 370 million people travelled by shinkansen versus 107 million by air.

And its track record is sterling. There have been zero operation-related fatalities – not one person was injured after a shinkansen derailed in March following a magnitude-7.4 earthquake – and the average service delay is under one minute.

Fraught beginnings

Things did not begin rosily for the bullet train, however.

Protests broke out as ground was broken in 1959 for the first line. The shinkansen was seen as expensive, useless and potentially anachronistic in an age of cars and aeroplanes.

Activists were also upset by the indiscriminate acquisition of land that included fertile agricultural fields, forests and religious sites.

But the line soon became a potent symbol of Japan’s technological rise from the ashes of World War II.

The first shinkansen had a maximum speed of 210kmh, traversing the 500km between Tokyo and Osaka in four hours, down from the six hours and 50 minutes it had taken with a limited express service.

“At the time, Japan was far from a wealthy country. But the shinkansen not only connected the two cities, it gave people dreams and hope,” said Vice-Transport Minister Satoru Mizushima.

It has dramatically shaped social life, by enabling single-day leisure or business travel and quick trips back home to visit relatives, thus fostering tourism, investment and growth.

Toyohashi, in Aichi, grew into an automobile hub with neighbouring Toyota, as factories and headquarters relocated. Atami, in Shizuoka, boomed as a resort town. Both cities are accessible by the multi-stop shinkansen services on the Tokyo-Osaka route.

More recently, a shinkansen service connecting Tokyo to Kanazawa, in Ishikawa prefecture, that launched in 2015 has been credited for the city’s reversal of a chronic decline in municipal tax incomes.

Constant innovation in the rolling stock – or a train’s engines and carriages – meant top speeds continued to increase. Today, the shinkansen connecting Tokyo and Osaka runs at a top speed of 285kmh, with travel time slashed to two hours and 21 minutes at the fastest.

The fastest shinkansen in Japan, with a top speed of 320kmh, runs between Tokyo and Shin-Aomori in the north-east.

Over the decades, Japan has grown its HSR network to around 3,000km in a total land area of 377,900 sq km, with Kagoshima, the southernmost prefecture on mainland Japan, connected to Hakodate in Hokkaido, the northernmost prefecture.

In 2030, the network will be extended to Hokkaido’s capital Sapporo, via the ski paradise of Niseko and Kutchan.

Behind the pristine safety and punctuality record are drivers and conductors who undergo vigorous training using simulators that test their reactions in unforeseen circumstances, as well as a rigorous maintenance process.

Trains are regularly serviced, including at the Hamamatsu Workshop, where they are completely overhauled every 36 months, or 1.2 million km travelled, whichever comes first, said workshop general manager Takashi Sugiyama.

Bogies are inspected every 18 months, or 600,000km travelled, while trains must undergo regular inspection every 45 days, or 60,000km travelled, he added.

“Rolling stock deteriorates with use, and the overhaul restores its functionality,” he said. “In the overhaul process, each train is taken apart right down to equipment and parts level and precisely inspected, before being reassembled.”

Train carriages are decommissioned after 13 to 15 years.

Further innovations

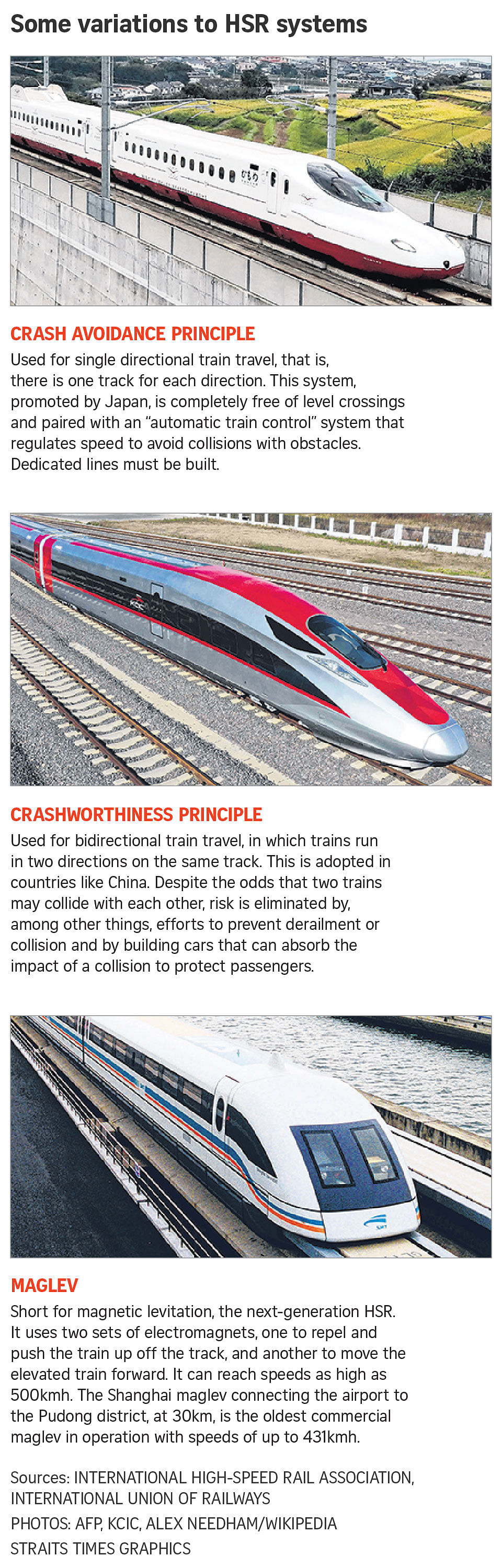

Within the decade, the shinkansen is going to get a major upgrade with the launch of a superconducting magnetic levitation (maglev) line between Tokyo’s Shinagawa and Nagoya stations.

When expanded to Osaka, it is expected to link up a large economic zone to give Japan’s stagnant economy a boost.

There may be delays to the planned launch in 2027 due to environmental impact assessments in Shizuoka Prefecture along the route, but when it opens, travel time between Tokyo and Nagoya will be cut from one hour and 34 minutes to 40 minutes with four stops in between.

The maglev will be expanded to Osaka by around 2037, with travel time between Tokyo and Osaka cut from two hours and 21 minutes to just one hour and seven minutes. The cost of the entire project is estimated to be nine trillion yen (S$88 billion).

Research into the technology began as early as 1962, with tests having been run since 1997.

Comprising superconducting magnets on the rolling stock and coils on the ground, the train is levitated 10cm off the ground and propelled forward and backward by magnetism.

While it has a proven top speed of 603kmh – certified by the Guinness World Records as the world’s fastest in 2015 – the operational maglev will run at speeds of 500kmh.

When fully operational, the maglev will connect the three largest metropolitan areas of Japan – Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka – within an hour and 10 minutes to create what is touted as a “super-mega region”.

This is home to 60 per cent of Japan’s overall population and 66 per cent of its economy, with a gross domestic product of 320 trillion yen in 2021 – higher than France’s 299 trillion yen – according to Mr Koei Tsuge, chairman of the Central Japan Railway Company.

“With more convenient and frequent travel, we can envision an economic impact beyond our expectations. This can relocate industry and decentralise the functions of Tokyo, in essence, shrinking Japan,” he said.

Professor Emeritus Shigeru Morichi from the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies said: “Our economy has been effectively stagnant for 30 years. Japan has lost some of its energetic spirit, and the maglev can be a trigger for its reinvigoration.”